Gold Classics Library Selection

Britain’s Gold Sales ‘a Reckless Act’

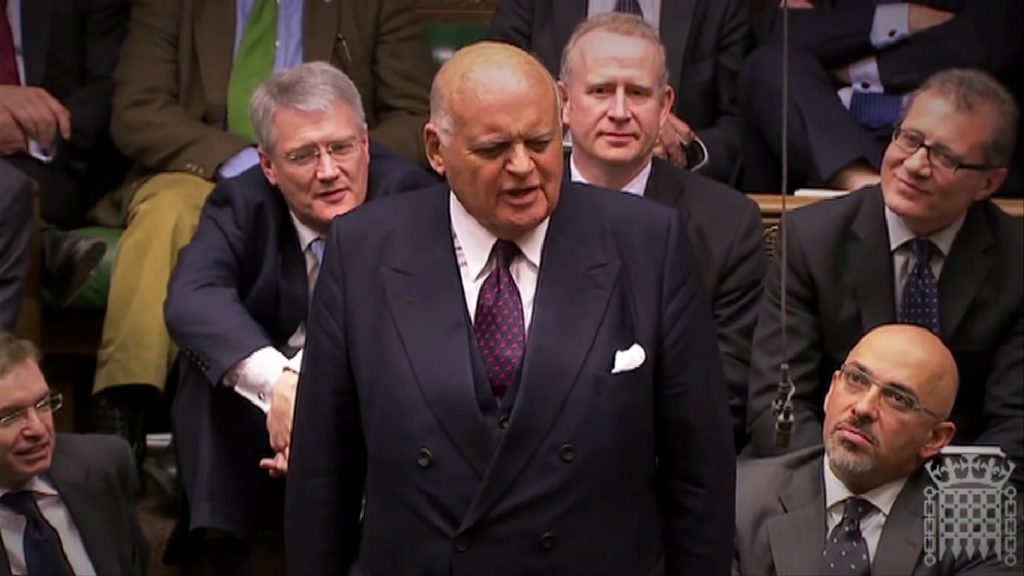

(Sir Peter Tapsell’s speech before the House of Commons, June 16, 1999, on the partial sale of United Kingdom’s gold reserves)

Editor’s note: In 1999, as a member of the British parliament, Sir Peter Tapsell argued vigorously to keep the government from selling off over half of the country’s gold reserves. Previously, in the 1980s, Tapsell had managed a gold bullion fund, “valued at many hundreds of millions of dollars for the Sultan of Brunei, Sir Omar Saifuddin” – at the time one of the single largest private gold hoards on Earth. Though his argument before the House of Commons failed to stop the sales, it goes down as one of the most eloquent appeals ever made on the merits of gold ownership for nation states and individuals alike.

Gold Sales

HC Deb 16 June 1999 vol 333 cc307-26

Sir Peter Tapsell (Louth and Horncastle)

I am glad to have the opportunity to initiate a debate on the proposed sale by the Bank of England of more than half of this country’s gold reserves. That decision was announced by the Treasury on 7 May and has been widely and critically discussed in the financial press, but the Government have been strangely reluctant to defend it or explain it in any detail to the House.

I should start by making it clear that I have no personal financial interest in the value of gold. I have never purchased any gold bullion, gold sovereigns or shares in any gold mining company for myself, and I have no connection with any mining company or any part of the jewellery trade. However, I have always taken a keen academic interest in the economic role of gold, which has been of importance in every society in recorded history.

In the 1980s, in my capacity as a stockbroker, I was required for some years to manage a gold bullion fund, valued at many hundreds of millions of dollars, for the previous Sultan of Brunei, Sir Omar Saifuddin. I was therefore able to add practical knowledge of the gold bullion market to my academic and political studies of it.

I regard the decision to sell 415 of the 715 tonnes of our gold reserves as a reckless act, which goes against Britain’s national interest. The sale of that crucial element of the United Kingdom’s reserve assets will weaken our scope to operate independently, reduce our influence in international financial institutions and diminish the United Kingdom as a world financial power.

I shall briefly set out eight of my main reasons for opposing the decision. Later in my speech, I shall expand on some of those and add a few more. First, a move such as the one announced on 7 May was always likely to destabilise the gold price, as Britain is a leading G7 country whose example is likely to influunce0othur countries and because it was not expected to sell gold. Market sentiment has become overwhelmingly negative and the price has collapsed from $287 per fine ounce immediately before the announcement to $259 at the fix yesterday—a fall of 10 per cent. That has reduced the value of our gold reserves in a little over a month by about $650 million, from $6.5 billion to $5.85 billion at current prices. The Chancellor’s announcement has so far cost this country’s taxpayers over £400 million, which is more than the cost to us of the Kosovo war.

Secondly, the decision reduces our monetary independence. For a country to hold gold is always and everywhere seen as an affirmation of independence and monetary sovereignty. We are told that the decision is not connected with preparations for joining the euro, but if we were to join—the Treasury has said that 40 per cent. of the proceeds from those gold sales will be invested in the euro—and if the euro were then to collapse or we were obliged to leave in the future, the absence of significant gold reserves would make it much more difficult to establish the credibility of any new currency that we had to set up.

Thirdly, the decision smacks of short-termism. In their foreign reserve policy, Governments and central banks are supposed to act in the long-term interests of their country. It is true that on a short-term view, gold has not performed well purely as an investment in the past 20 years, but that reflects mainly the success, which is possibly temporary, of central banks in controlling inflation. No Government can be sure that price stability will endure for ever.

Fourthly, the decision is a threat to the London gold market because it reduces the Bank’s ability to act as what is known as a swing lender to the market. Many market participants believe that after the sales have been completed, the Bank will not have enough gold to fulfil its function as a swing lender and so retain the centre of the world gold market in London.

Fifthly, about 20 per cent. of the proceeds are to be invested in yen—so the Treasury tells us. Yet, by lending gold we could earn a better return, as the rate of interest on gold is higher than that on yen investments. I have already mentioned that 40 per cent. is to be invested in euros, yet we hear that the Netherlands is already taking steps to build up its foreign reserves to protect the guilder if the euro were to collapse.

Mr. Robert Sheldon (Ashton-under-Lyne)

The hon. Gentleman said that the interest earned on gold was greater than that on other foreign assets—

Sir Peter Tapsell

On yen.

Mr. Sheldon

I did not understand that; I am not sure what the interest on gold is.

Sir Peter Tapsell

The deposit rate in Japan at the moment is about 0.5 per cent., and the normal interest rate on gold is l per cent., which is double.

Sixthly, the concept of reserve management that lies behind the decision is deeply flawed. The Treasury has argued that gold makes up almost half of the unhedged or “net reserves”, to quote its press release. That concept of net reserves is arbitrary, as it all depends on what liabilities are deducted from gross assets. So far as I have been able to discover, such a concept has never been used by any other country; international gold figures are always quoted in terms of gross reserves. After the sale of 415 million tonnes of our gold, as is intended—125 million tonnes straight away and 290 million tonnes in the medium term—our gold reserves will be only 7 per cent. of our gross reserves, which is slightly less than those of Albania.

Seventhly, the history of the past 50 years shows again and again that United Kingdom Governments have from time to time been forced to intervene, either to stop the

309

pound rising too quickly or, more frequently, to try to slow a fall in the pound. It makes no sense to throw away a key element of that instrument. No other major country is doing so. In relation to imports, our reserves are already far smaller than those of comparable countries.

Eighthly, in the view of many leading bullion dealers, the method of sale chosen—auctions—is also ill advised. Whatever the merits of transparency, the UK taxpayer has certainly lost substantially from the drop in the price consequent on the announcement and the resulting fall in the expected proceeds from gold sales. Each bi-monthly auction of our gold—the first of which will be held as soon as 6 July—is likely to worsen that problem.

Mr. Andrew Tyrie (Chichester)

Given the great criticism of the introduction of gilt auctions, which have turned out to be successful, and given that the Government have decided to sell the gold, does my hon. Friend think that there is a better method of selling it than by auction?

Sir Peter Tapsell

I did say that there was a problem about transparency. When examined on the problem of method of sale by a committee in Congress the other day, Mr. Greenspan said that it was very unsatisfactory. Incidentally, he is completely against selling gold. He said that, whereas Mr. Buffet could buy silver, and when the report came out three months later that the price of silver that he had been buying had risen, he could sell his silver at a profit, Mr. Greenspan did not think that major central banks should proceed along those lines. That is of course the problem and why, no doubt, the Bank of England has found it necessary to announce to the world that it will keep selling every other month. The penalty one pays for that—for psychological reasons mainly—is a substantial fall in the gold price.

In giving evidence to the Treasury Select Committee recently, our governor said that the fall in the price of gold had been greater than he had anticipated and he thought it to have been overdone. The authorities should have foreseen that the psychological impact of the Bank of England, of all institutions, announcing that it would take such a course of action, would be very adverse on prices.

That brings me to comment on the historical background. The argument about gold has gone on for centuries. The Bank of England was founded in the reign of King Charles II and, as early as 1717, it decided to put our reserves into gold. That was done, interestingly, on the advice of Sir Isaac Newton, who was born and brought up in Grantham in Lincolnshire—my home county. It is very appropriate that my hon. Friend the Member for Grantham and Stamford (Mr. Davies), whom I congratulate on his promotion, should today be sitting on the Opposition Front Bench.

Sir Isaac Newton, Lincolnshire’s most famous son—the county has had a famous daughter since, but I shall pass over that rather more controversial point—proposed that, in effect, the Bank of England should put its reserves into gold. The matter was debated at length in the House of Commons and was approved, only after great controversy, in December 1717. Thereafter, many other central banks and other countries argued about whether they would put their reserves into gold, silver, a mixture of the two, or some other form. People have often forgotten that the great economic debate of the second half of the 19th century all over the western world was over bimetallism—in effect whether a country ought to have its reserves in gold or silver.

That debate culminated in the presidential election of 1896—the most ferociously fought and perhaps most famous of all American presidential elections, which centred on whether the United States should put its reserves entirely into gold or a mixture of gold and silver. At the Democratic convention of 1896 in Chicago, William Jennings Bryan made his famous two-hour speech on the subject, in which he used the phrase about mankind not being crucified on a cross of gold—one of the greatest speeches ever made. But William Jennings Bryan lost the presidential election by 500,000 votes, and William McKinley, the pro-gold winning candidate, ensured that the United States shortly thereafter went on to the gold standard. The Federal Reserve Board was originally established to look after the gold.

I mention all that—there is a great deal more to it; many histories of the period have been written in economic terms—to show that what we are discussing is of immense importance and has always been regarded as such. We tend in our debates in this House to think only of more recent events, such as Britain’s return to a gold link in 1925, our retreat from it in 1931, the American abandonment of a fixed relationship between gold and the dollar in 1971 and about whether, today, Britain should join the single European currency—the arguments over which are very closely related to those I have been describing. It is very significant that, as recently as last Thursday, the British people were, in effect, being asked to vote on matters closely related to the subject of this debate.

Sir Teddy Taylor (Rochford and Southend, East)

Does my hon. Friend think that the whole business of the instruction given to the Bank of England to switch from gold largely into euros is simply a pathetic attempt—a device—to give credibility to, and boost the value of, the Euroflop currency?

Sir Peter Tapsell

I said that I thought that that was one of the possibilities. It is certainly among those that commentators have discussed. I have never been an advocate of the conspiracy theory of history, and I tend to think that slightly more complicated issues are involved than that, but I shall return to the issue of the relationship with the euro.

The point of my remarks about the history of the issue and the fact that it has been passionately argued about for centuries, was to show the amazing contrast with the almost furtive way in which the announcement was made on 7 May. One might have expected that the Chancellor of the Exchequer would make the announcement at the Dispatch Box—but far from it. The announcement came on a Friday afternoon, in answer to a planted written question by the hon. Member for Hove (Mr. Caplin), who is not even in the Chamber today, and who has not yet had time to establish himself in the House as a leading authority on international monetary affairs. It seems extraordinary that it should have been done in that way.

Moreover, the written answer given by the Economic Secretary to the Treasury—who I am glad to see in her place—was extremely cursory and brief, and contained only a very small part of the story. As is characteristic of the present Government, the information was contained in two press releases, each several pages long, one from the Treasury and one from the Bank of England, giving a great deal of information about the Government’s intentions—vastly more than was given in the written answer—and then press conferences were held at which many questions were answered. The House of Commons was sidelined again, on this very important issue. For those reasons, the way in which the announcement was handled was disgraceful.

The immediate effect has been the loss of £400 million of our taxpayers’ reserves, and so far the only beneficiaries of this event have been the foreign finance houses, which have been shorting the gold market. As I said to my hon. Friend the Member for Rochford and Southend, East (Sir T. Taylor) in all friendliness, I am not a subscriber to the conspiracy theory in any aspect of life, so I shall not go into detail about the conspiracy theories that are widely circulating in the City about that shorting of the gold market, but it is often said that some of those famous foreign finance houses have shorted gold to a huge amount—vastly greater than the tonnage of sales contemplated by the Bank of England—and that it was therefore vital for them for the gold price to fall substantially so that they could close their positions and take huge profits. I do not know whether that is true, although I think that there is no doubt that several finance houses have been shorting gold in a very large amount, so I suspect that the financial press will pursue that point with vigour in the days and weeks to come.

Everyone remembers how Mr. Soros precipitated the last Russian economic collapse by publicly declaring that, in his view, the rouble was overvalued. Not long after, he said that his funds had lost $800 million as a result of that collapse in the Russian market. I do not know whether our Chancellor has been inspired by Mr. Soros to follow in that path, but he seems to have produced a somewhat similar effect.

I have the greatest respect for the Bank of England, and it is perfectly clear that the Bank did not take the decision. I doubt whether it even favours it. It was given an instruction by the Treasury and when, at the press conference, a Bank of England spokesman was asked by a journalist whether the Bank thought that this was a good idea, that spokesman replied: “It was a political decision.” I hope that, when the Economic Secretary replies, she will—as has not yet been done—give us all the reasons for this political decision, because the Bank of England, despite its many merits, has not always been clever at playing the market, and Governments in general are not usually very clever at playing markets. The last time that the Bank of England sold gold in sizeable quantities was in 1971, at about $40 per fine ounce. The price of gold then rocketed, reaching a peak of $850 by 1980. So when the Bank of England last sold gold, it did so at the worst possible time, and I do not know whether anyone has ever worked out the extent to which the British taxpayer was deprived of profits by that decision.

I strongly suspect that the Bank of England is now again selling at pretty near the bottom of the bear market—or what would have been the bottom if it had not made its announcement. As I said in my personal declaration of non-interest, I have never owned gold, but in recent weeks, as the gold price has declined, I have said jocularly to friends that, if I won the national lottery, I would put half the proceeds into gold bullion with the price below $300. I believe that many people who have followed these matters with interest were thinking that it was about time that the finance houses closed their short position. It is extraordinary, as a matter of market judgment, that the Treasury and Bank of England should have chosen this very sensitive moment to step in and deal that damaging blow to market confidence.

The answer that other countries have given is extremely interesting. We have not really been told the Government’s reasons for their sale, but on 26 May the Prime Minister, in answer to a question by my hon. Friend the Member for Macclesfield (Mr. Winterton), said that “throughout the world countries have been selling gold in order to diversify their reserves.”—[Official Report, 26 May 1999; Vol. 332, c. 351.]” That is really the only ministerial statement that has been made, and that was elicited by an omnibus question by my hon. Friend.

The Prime Minister’s answer was most misleading, as I shall show. Of the more than 100 countries that hold gold, only five, with relatively small economies, have sold. No other major economy has sold gold or intends to sell it. It must be borne in mind that the losses imposed on the British taxpayer by the Chancellor’s decision have also been suffered by the French, German, Italian and American taxpayers. I cannot imagine that, when the Governor of the Bank of England next attends a cocktail party in Basle for the monthly meeting of the Bank for International Settlements, he will be the most popular chap there.

Mr. Christopher Gill (Ludlow)

I am grateful to my hon. Friend for giving way. Several times he has instanced the potential loss to British taxpayers as a result of the Bank of England selling its gold reserves. I understand that point and entirely agree with him. However, is there not another consideration? Gold and money are a store of value. If, by selling gold, the Bank of England put that value into another currency that seems unlikely to preserve the store of value for British taxpayers, would that not have a doubly deleterious effect on taxpayers’ funds, first by making a loss on the transaction, and secondly by investing the proceeds in a currency where the store of value will not be retained?

Sir Peter Tapsell

I entirely agree with my hon. Friend. I shall deal with that point later, as I intend to make a fairly comprehensive speech about gold. The point about gold, as my hon. Friend says, is that it is no one else’s liability. As soon as one puts money into other stores of credit, other factors are at work.

I return to the Prime Minister’s claim that so many other countries were selling gold. No major country is planning to sell gold, and other countries must be extremely irritated by the way in which the British Government have handled the matter. A series of central bank governors of major countries have issued similar statements on the subject. For example, on 19 May the governor of the Bank of France, Mr. Jean-Claude Trichet, said: “I will simply say that as far as I am aware—and this is not just the position of the Bank of France and our country, but also the position of the Bundesbank, the Bank of Italy and of the United States, and these are the four main gold stocks in the world—the position is not to sell gold.”

The chairman of the US Federal Reserve bank, Mr. Greenspan, speaking to the House banking committee in Washington the following day, 20 May—there was obviously co-ordination between the central bank governors—said: “We should hold our gold. Gold still represents the ultimate form of payment in the world. Germany in 1944 could buy materials during the war only with gold. Fiat money in extremis is accepted by nobody. Gold is always accepted.” Those were the words of Mr. Greenspan, the world’s most admired central bank governor. That takes up exactly the point made by my hon. Friend the Member for Ludlow (Mr. Gill). It is therefore not open to Ministers to say, as the Prime Minister said, that countries of our standing in the world are all selling gold.

Mr. Edward Davey (Kingston and Surbiton)

I am grateful to the hon. Gentleman for giving way. Will he confirm that the average annual sales of gold by national central banks across the world over the past decade has averaged 300 tonnes a year—almost three times the amount that the Bank of England proposes to sell?

Sir Peter Tapsell

That is perfectly true, but the holdings of gold by central banks are only 6 per cent. lower now than they were 20 years ago. Other central banks, such as those of Russia and China, have been buying gold. It ic perfectly true that the amount of gold that the Bank of England is selling is relatively small, but the psychological impact on the market is disproportionate.

The Bank of England was the bank that set the lead. Together with Rothschilds and Mocatta, it has always been at the centre of the world gold market ever since 1717. When the Bank of England says that it is selling gold, the tonnage that it is selling is less significant than the psychological impact of that on the rest of the world.

It is true that five countries—Australia, Canada, Argentina, Belgium and the Netherlands—have each sold more than 100 tonnes of gold in recent years, but in no case have those countries done so to diversify their reserves or to increase the technical efficiency of their management. They have all had other reasons.

It would take far too long for me to go into detail about the position in each country, but briefly, Australia sold because there was a mineral price slump in the world at the time and it had an economic crisis. In any case, Australia has very large quantities of gold underground, not yet dug up, so it does not have to worry too much about its gold reserves above ground.

Canada, which also has very large quantities of gold underground, sold in preparation for joining the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement at a time when its currency was under pressure. Argentina has a currency board-type arrangement, which is quite different from a central bank, and is in effect part of the dollar area, so the considerations about gold that would be important to other central banks do not apply. Belgium sold in order to satisfy the debt:GDP ratio criteria in the Maastricht treaty.

The Netherlands is widely believed to be concerned about the possibility that the euro may collapse entirely. It was interesting that the new president of the European central bank, who is a distinguished former governor of the Dutch central bank, went so far as to say publicly the other day that he thought, and had so advised, that the euro was introduced two years too early. The Dutch, who have traditionally run a strong and successful currency since the war, are extremely concerned about the euro. It is said that they have been trying to build up foreign reserves outside the euro, in case the euro collapses.

I shall deal now with the question why central banks should hold gold. I hope that the Minister will reply particularly to these points. It is not just a few of us specialists in the House who are interested. I assure her that the markets generally are extremely interested in the subject. I have never received so many messages from total strangers as I have in recent days, since the title of the debate appeared on the Order Paper. The financial press is also very interested. It is time that the Government explained in detail the reasons for their policy.

Why do central banks hold gold? First, as I said to my hon. Friend the Member for Ludlow, because it is no one else’s liability. If one invests in the bonds, paper and Treasury bills of other countries, one can suddenly find that one’s asset has greatly diminished.

A taxi driver said to me two days after the Government’s announcement, “Why are we selling our gold? I don’t want to sell my gold and be given toilet paper money in return.” That is sound economics. The man in the street may not have read his Keynes, but he has a good grasp of the realities of economics.

If, as the Bank of England proposes to do, it puts 40 per cent. into dollars, 40 per cent. into euros and 20 per cent. into yen as a result of the sale of the gold, it will be speculating. We have seen a tremendous collapse in the yen, and the American dollar has gone up and gone down periodically, so the Bank of England is, in effect, playing the market.

To return to an earlier intervention from my hon. Friend the Member for Chichester (Mr. Tyrie), the argument about transparency also applies to currencies.

When a currency is under pressure it is difficult for a central bank to start to sell it. It is regarded as near-treachery. When the British and French currencies came under serious pressure in 1992, the US Fed and the Bundesbank were expected to support them, not to sell them. There has been some controversy over whether the Germans supported our currency as vigorously in 1992 as we think they should have done. I think that my noble Friend Lord Lamont has views on that subject, which may come out in his book to be published shortly.

In theory, central banks are supposed to co-operate with each other so that when a particular currency comes under pressure, they rally round to support it. The idea that by diversifying into foreign currencies the British Government will suddenly have much more flexibility is an illusion. I very much doubt whether the Government would like the market to see them selling their newly bought euros because they thought that the euro was about to collapse even further. That would not help the Prime Minister’s position in the centre of Europe.

Mr. Nick St. Aubyn (Guildford)

Does my hon. Friend agree that, in selling our precious gold reserves and putting the money into the collapsing euro, the Government will be showing much more support for the euro than those who belong to it showed support for us in 1992?

[Continues below]

A word on USAGOLD – USAGOLD ranks among the most reputable gold companies in the United States. Founded in the 1970s and still family-owned, it is one of the oldest and most respected names in the gold industry. USAGOLD has always attracted a certain type of investor – one looking for a high degree of reliability and market insight coupled with a professional client (rather than customer) approach to precious metals ownership. We are large enough to provide the advantages of scale, but not so large that we do not have time for you. (We invite your visit to the Better Business Bureau website to review our five-star, zero-complaint record. The report includes a large number of verified customer reviews.)

Sir Peter Tapsell

Yes, but one should not conduct economic policy on a tit-for-tat basis. Incidentally, we would all be wise not to assume that the euro will continue to weaken for ever. I can speak with a free conscience on this matter, as I voted against every clause of the Maastricht treaty. Indeed, there would never have been a European central bank if three more of my colleagues had joined me and others in voting against the paving motion.

The fact is that the euro now exists and it is just another currency, as I always predicted it would be. Currencies go up as well as down. In my view, the dollar is today over-valued and the euro is under-valued. The fact that in a few weeks or months the euro will probably go up against the dollar and the pound does not strengthen the argument for joining it. Euro-sceptic that I am, I do not believe that it would be in the British national interest for the euro to collapse because that would lead to chaos in Europe and would be damaging for our export markets.

The second reason why one should hold gold reserves is because they build public confidence. Market research carried out last year by one of the world’s leading research companies in several European countries showed overwhelming support for countries maintaining gold reserves: 76 per cent. of respondents in France, 72 per cent. in Germany and 75 per cent. in Italy said that gold reserves are important in supporting a strong economy; 84 per cent. in France, 83 per cent. in Italy and 65 per cent. in Germany agreed that having a strong gold reserve helps to bolster public confidence on which economies depend. Similar results—70 per cent. opposing the sale—were received when the British public were questioned on the subject in a recent opinion poll.

Another reason why central banks should hold gold is that, over the very long term, gold maintains its value. In 1900, the value of gold was almost identical to its value in 1717. Although its soaring up to $850 in 1980 artificially over-priced the market—it has been coming down ever since—gold holds its long-term value, as we have seen throughout history. On 27 May, the Financial Times pointed out that $35 an ounce, which was what gold was in 1971 before President Nixon and Treasury Secretary Connally broke the link between the dollar and gold, would be equivalent to $281 today. Thus, despite the fact that gold is at the bottom of a long bear market, it was still worth more than $35, in today’s terms, when the Government made their announcement. It has now dropped below that figure.

Mr. Sheldon

It all depends where one takes one’s basis. However, $35 an ounce was the price before the war, so the hon. Gentleman must take that as his basis as well.

Sir Peter Tapsell

The right hon. Gentleman is a distinguished former Treasury Minister, but I must point out that that was not the price before the war. The price of $35 an ounce was fixed at Bretton Woods in 1944. In 1932, President Roosevelt devalued the dollar against gold and we devalued, under a Labour Chancellor, in 1931. However, the $35 that was officially linked to gold—which put the whole world not on a gold standard but on a dollar standard between 1945-71—dates from Bretton Woods. I have not argued that gold has been a particularly good market investment in recent years, but it has not been as bad as many people would suppose. Even since 1971, it has roughly held its value in line with inflation.

My next argument for central banks holding gold is that a country’s reserves should be diversified to minimise risk. Research shows that gold is an ideal portfolio diversifier. When I was given the Brunei fund to manage, I had to go on a crash course because I knew nothing about gold management. I took much expert advice and even commissioned, at great expense, advisers to give me an idea of how much gold should be in a portfolio. The boffins who deal with those matters believe that, over a long term, the ideal gold holding in a major portfolio is about 20 per cent. That is because gold is an ideal diversifier as its returns are what is technically known as “negatively correlated”, which means that they operate in a counter-cyclical manner. When bonds and equities fall in price, gold tends to go up.

Gold prices are much more volatile than other market prices. It is not unusual for gold to go up 2 or 3 per cent., or down 2 or 3 per cent. in a single day. If Wall street falls by 2 or 3 per cent. in a single day, it is headline news throughout the world. Thus gold has a stabilising effect in a long-term portfolio.

Gold is also the asset of last resort. Although it is needed in good times, it can be vital when times are difficult. The last sale of gold in France was in 1969 to deal with the financial consequences of the May 1968 uprising. In Portugal gold was last sold following the 1975 revolution. More recently, in 1991 India used its gold reserves to borrow $1 billion to avoid default.

I have already quoted Mr. Greenspan, who said that in 1944 Germany could not buy anything except with gold. In a real crisis, there is no doubt that gold is important. It is not just my taxi driver who takes that view. When I was in Vietnam last year, everybody told me that every Vietnamese peasant has gold underneath his floorboards or his straw because the Vietnamese have no confidence in their currency. We tend to talk about gold in terms of official reserves, but a lot of unofficial gold is hidden in China and Vietnam and, one is always told, in France—although I have a French wife and I have not yet managed to discover her gold hoard. It is widely believed that people hold gold all over the world secretly, against the possibility of disaster, which is a tremendously important market consideration. That is what is meant by the psychology of gold and it is extraordinary that the Bank of England should have taken this decision, and the way that they have done so.

I do not wish to go into the question of International Monetary Fund gold sales in any detail, because that is a separate, although obviously related, subject. The IMF is not a central bank. It is ironic that the Chancellor, who is understandably keen to help the poorer nations of the world, seems also to be keen to persuade the IMF to sell gold. He hopes that it will do so, but many poorer countries would be extremely hard hit by that.

Hon. Members who are interested might care to read the recently published pamphlet entitled “Gold mining’s importance to sub-Saharan Africa and heavily indebted poor countries”, because 41 HIPCs mine gold, and it is an extremely important part of the exports of nine of those countries. Curiously enough, the sale of IMF gold, if it depressed the price of gold still further, would seriously and adversely affect many of the poorest countries.

The sale of our gold will not increase the size of our reserves; they will remain the same, so that argument cannot be used. Many countries feel that they ought to be building up their reserves, and they are all trying to do so. An extraordinary aspect of the situation is how dangerously low Britain’s net reserves are. Their net value on 7 May was only $15 billion. A more sensible policy than selling gold would be to build up our reserves by buying dollars and other currencies with our sterling. That would help to lower the exchange rate of sterling, which is a desirable objective at present, and increase our reserves of foreign currencies, which the sale of gold will not achieve.

Mr. Tyrie

In view of the experience in the 1990s with the huge movements of global capital, does my hon. Friend believe that open market operations are an intelligent way in which to try to alter the value of a currency?

Sir Peter Tapsell

I would not normally take that view, but our long-term economic aim ought to be the building up of our reserves. That is what every country wishes to do, and many of them are pursuing that. Our reserves in relation to our imports are very low, so any step that we can take to build up our reserves will be welcome.

I have mentioned the aspects of pubic opinion. I am not one of those who thinks that one should follow focus groups and so on, but it is overwhelmingly evident that public opinion in this country is opposed to the whole policy of selling gold by 5:2. The Government will have to be persuasive if they are to change that view.

There have been previous attempts to reduce the role of gold in central banks. The last was the introduction of special drawing rights. At that time, I happened to be an adviser to the monetary authority of Singapore. I went to see Dr. Goh Keng Swee, who was then Singapore’s Finance Minister and who, in my experience, had the most subtle and brilliant financial mind of any Finance Minister or central bank governor I have ever known. I said to him, “Dr. Goh, will Singapore take SDRs?” Dr. Goh replied, “I have no intention of putting a paper tiger into Singapore’s tank.” That is a slogan worth keeping in mind.

The whole point about gold, and the quality that makes it so special and almost mystical in its appeal, is that it is universal, eternal and almost indestructible. The Minister will agree that it is also beautiful. The most enduring brand slogan of all time is, “As good as gold.” The scientists can clone sheep, and may soon be able to clone humans, but they are still a long way from being able to clone gold, although they have been trying to do so for 10,000 years. The Chancellor may think that he has discovered a new Labour version of the alchemist’s stone, but his dollars, yen and euros will not always glitter in a storm and they will never be mistaken for gold.

10.26 am

Mr. Edward Davey (Kingston and Surbiton)

I congratulate the hon. Member for Louth and Horncastle (Sir P. Tapsell) on keeping to a fairly balanced view when he developed the theory of the role of gold in a modern economy. However, I disagree with his conclusions.

In answer to my intervention, the hon. Gentleman talked about the psychological importance of this sale of gold and explained the psychological role of gold in monetary economics. He was right to focus on that, because gold’s main contribution in the modern monetary economy is that it is, at the last resort, the store of value and the provider of assistance in underpinning market confidence. However, many other commodities and assets retain value for investors, businesses and Governments and there are many other ways of maintaining market confidence in a modern economy, from regulation to the lessons of history.

At the end of this century, many participants in the financial markets—and in all product and labour markets, for that matter—have much greater confidence in the ability of capitalism and financial capitalism to deliver success. That was not the case centuries ago, when gold made a much more important psychological contribution. The lesson of history is that we do not need gold to underpin confidence and value. The role played by gold has been declining, which means that the hon. Gentleman’s point about its psychological contribution is much less strong today.

I completely agree with the hon. Gentleman that, in the past, gold was absolutely vital—in the early days of financial capitalism, it was crucial—but the role that he wishes to attribute to it is not as strong as he suggests.

Mr. Gill

Does the hon. Gentleman think that these matters should have been discussed in the House before the decision to sell was made, given that money has been put aside in reserves by the taxpayer? The taxpayer clearly has a view, as my hon. Friend the Member for Louth and Horncastle (Sir P. Tapsell) explained in his excellent presentation. There is also the question whether the taxpayer feels that that store of value, which belongs to him, has been preserved by putting the proceeds of the sale of gold into other investments. Does the hon. Gentleman think that the House should have been granted a debate on these important matters before the Government took the decision to sell the gold?

Mr. Davey

I do not agree with the hon. Gentleman about that. One of the criticisms that can be made of the Government is that they were too open and transparent about the sale of the gold, and that that has moved the market price. I do not subscribe to the criticism that has been made of the Bank of England’s approach, because I think that the way in which it has set out these sales over the next 12 months will help to bring order and stability to the gold market, which, as has been said, is characterised by volatility.

The hon. Member for Ludlow (Mr. Gill) tempts me a little. The problem with the House is that we do not analysis Government expenditure in enough detail. The House grants £300 billion to £350 billion of public expenditure without full debate. We should scrutinise the Government on that expenditure: not on technical gold sales. There is a strong argument for not having a full debate on gold sales, because that could move markets. The role of gold can be overplayed. That is not to say that gold markets are not important and that we should not have gold reserves: of course we should. I do not pretend to have all the financial knowledge before me properly to take a view about whether the Bank of England is right in its portfolio adjustment, but I concede that the people who are overseeing the portfolio of assets that the Bank of England holds in its vaults must from time to time decide whether to make changes and adjustments. It would be nonsense if the Bank of England were to hold static for ever a particular set of assets in particular proportions.

Mr. St. Aubyn

Does the hon. Gentleman think that it is right that the Government took this decision without giving any thought to the effect on the developing world and on the gold price? Jobs are now being lost in very poor countries as a result of this decision.

Mr. Davey

I am grateful to the hon. Gentleman for raising that issue, because that is also one of my concerns. Will the Minister explain a little more the thinking behind this decision? Now that we have this debate, it would be sensible for the Government to outline the thinking behind this sale, particularly with respect to employment in developing countries that have gold as one of their key commodity exports and the Government’s policy to promote the sale of gold from the International Monetary Fund to help to deal with debt relief in poor countries. I hope that all parties in the House support that policy, because it is crucial that we try to forgive the debts of the poorest countries—the debts that are deemed to be, in Jubilee 2000 language, unpayable. The Government have made a good start, and I hope that they go further. It would be wonderful if the Minister were to announce today further gold sales for that purpose, but I doubt that she will do so.

I hope that the Minister will explain the thinking to reassure us that the left hand knows what the right hand is doing, that there is some co-ordination between the Treasury and the Bank of England on all aspects of policy, and that the policy on assisting debt relief has been linked to the policy of portfolio adjustment at the Bank of England. If those decisions are not co-ordinated, the Government are not doing their job properly.

I congratulate the hon. Member for Louth and Horncastle on securing this debate. It will help the House to focus on the role of gold in a modern economy. I take a different view from his. In international monetary economics in the late 20th century, money creation and the complexity of global financial markets is such that the role of gold is much diminished. Money creation in modern financial capitalism is almost endogenous and does not rely on a stock of yellow commodity lying in the central bank’s reserves. The workings of financial capitalism have almost no relation to gold.

The hon. Gentleman is right that, in extremis, if the whole structure of financial capitalism were to fall to the ground with a nuclear meltdown of the financial markets, the role of gold would come to the fore. It is right for central banks to consider all potential future risks to ensure that our society and our economy can function even in such disaster scenarios. They should hold gold, but they do not need to do so as they have in the past.

I do not know whether selling 125 tonnes of gold over the next 12 months and buying yen, euro and dollar assets is the right portfolio adjustment. Not many hon. Members have the information and expertise to make that full analysis. However, I think that it is right that the Bank of England is considering how best to deploy its assets.

The total amount being sold is very small compared with the amounts that have been sold by other countries in recent times and that are expected to be sold in the future. Switzerland has announced future sales of 1,300 tonnes of gold, which is much greater than the amount that the Bank of England proposes to sell. We should put this matter in context, and should not get too hot under the collar about it.

10.36 am

Mr. Andrew Tyrie (Chichester)

I agree that more attention should be given to this subject. The Government should have called a debate, and I regret that they did not. I also agree about the mystique—”Goldfinger” is on television tonight, so it is an apposite day on which to hold this debate, and I have set my video recorder.

The key issue is whether gold can still play a monetary role. It used to play a big monetary role because people did not trust paper money. It played a crucial role in the development of the international traded goods sector in the 19th century. It was very effective, because it was difficult to cheat. It coincided with a period of stable prices in the 19th century. I say coincided because it was largely luck: it was because gross domestic product grew at roughly the speed of the monetary base—the increase in the amount of gold available—and thereby serious deflation was avoided.

That history of success in the 19th century was carried over into the 20th, and gold was used as part of the stabilising function in the Bretton Woods system in 1944—the dollar link. When inflation created by the Vietnam war destroyed Bretton Woods, that should theoretically have led people to rush back to gold. They did a little, but no serious analyst suggested that gold should be brought back as the monetary base. There were more sophisticated arguments for commodity-based standards, which I think had some merit, but virtually no one, even during the crisis created by global inflation, thought that gold was the right way to go.

Since that time, gold has steadily fallen in price. Can gold once again play a role as a reserve currency? I do not think so. It is no longer a good store of value: we have seen that in recent years. I do not think that gold is a suitable vehicle for open-market operations, which are themselves far less relevant in an age of such huge global capital flows. Nor do I think that we will go back to gold as a vehicle for dealing with inflation, if that returns.

Gold is, as the famous phrase goes, a barbarous economic relic. I cannot believe that it makes good economic sense to spend a huge amount of money digging something up, turning it into ingots and then burying it again in vaults. These gold sales are not primarily a monetary issue. I note that the Monetary Policy Committee did not even discuss the matter. The case for the demonetisation of gold is strong.

I cautiously support the sales, but I am sorry that the Government have not moved more carefully. I do not think that there was any need to rush into these sales. We do not know whether the gold price will go down or up. My hon. Friend the Member for Louth and Horncastle (Sir P. Tapsell) said that he thought it was at a low point. He may be right, and he may be wrong—we do not know—but he could be right, and if he is right we should proceed more cautiously.

Mr. William Cash (Stone)

Will my hon. Friend give way?

Mr. Tyrie

If my hon. Friend will forgive me, I will not, because I have only two or three minutes in which to finish my speech.

I am a little worried that we will sell too quickly. It is a question not just of the amount, but of the speed. There are good arguments for believing that the gold price may continue to fall. The United States might start selling gold. Has the Treasury a view on whether major countries are now considering gold sales? Is there any suggestion that they might?

I think that gold will be used less in the 21st century as a store of value in Third world countries—Vietnam was mentioned earlier—and that will result in more gold coming on to the market. Improvements in mining techniques will almost certainly increase the amount of gold available. I worked in the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development for a while, and it was found to be profitable to “leach” the piles of slag that had already been used for gold mining, to obtain gold by means of more efficient industrial processes. The supply side points to a weak gold price for some time to come.

With great respect, I thought that my hon. Friend the Member for Rochford and Southend, East (Sir T. Taylor) was talking nonsense when he suggested that the Government might be selling in order to influence the price of the euro. They could do that perfectly well by using the forward book, with or without gold, as a reserve in the vaults. As I have said, I would like the Government to explain why so fast, and why so much.

10.42 am

Mr. Quentin Davies (Grantham and Stamford)

I congratulate my hon. Friend the Member for Louth and Horncastle (Sir P. Tapsell) on securing this short debate, during which he raised a number of points that it would be remiss of the House not to discuss seriously. He is a distinguished parliamentarian, and brings to the subject a wealth of professional experience as well as the depth of historical knowledge for which he is famed in the House. I never listen to him without learning something that I did not know before, and I certainly was not disappointed on this occasion.

The hon. Member for Kingston and Surbiton (Mr. Davey) also made some sensible points, and we heard a valuable—but sadly, owing to the shortage of time, all too short—contribution from my hon. Friend the Member for Chichester (Mr. Tyrie), who probably knows more about the subject than any other Member except my hon. Friend the Member for Louth and Horncastle.

The Government have left two questions in the minds of parliamentarians and the public. First, why did they decide to sell the gold? We are still no clearer about that, and I hope that we shall be clearer by the end of the debate. Secondly, why have the Government adopted such an astonishing method of conducting the sales?

Because the Government had not given us sufficient explanation, my right hon. Friend the Member for Horsham (Mr. Maude), the shadow Chancellor, wrote to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, but all that he received was a lot of waffle. The reply stated: “As we have been careful to explain this is a prudent restructuring of the reserves.” This is to do with “Prudent management of public finances” to achieve a “better balance in the portfolio.” Those are evasive answers. We need an answer to the question, why is it more prudent for gold to constitute 20 per cent. of the net and 7 per cent. of the gross reserves, rather than 40 per cent. and 17 per cent., or whatever the current figures are? We have heard no explanation of the factors that determined the Government’s course of action, and we badly need one.

Gold has traditionally been held as a reserve because its value is a negative function of the strength of the dollar, a positive function of inflation rates and a negative function of real interest rates. It is possible to construct a hedge against the dollar simply by holding other currencies, but there is no such obvious way of obtaining protection against a resurgence of inflation, a collapse of real interest rates or interest rates becoming negative again, as they have during all our lifetimes, that is better than holding gold. As my hon. Friend the Member for Louth and Horncastle pointed out, gold is a long-term insurance policy against contingencies that we do not foresee in the immediate future, but which could always return. We need to know why the Government have decided that they want to roughly halve that insurance policy. After all, 700 tonnes of gold is not very much for an economy the size of ours.

The Government must think that there is some reason for holding gold in the reserves, or they would have decided to get rid of the entire gold reserve. We need a clear explanation of why they think it prudent to hold a mere 300 tonnes. If they agreed with the arguments advanced by my hon. Friend the Member for Chichester, it would be logical for them to get rid of gold altogether; but they have not, and their actions lack credibility.

Do the Government have formal models for determining their management of the portfolio of the reserves? Is there a formal risk management model? If so, will they place it in the House of Commons Library, so that all of us, including the public, can learn on what the portfolio decisions are based, and why such adjustments are apparently required? After all, the Government are acting in an agency capacity, managing the taxpayer’s money.

The Minister must reply to the serious point made by my hon. Friend the Member for Louth and Horncastle. We cannot allow the rumours to grow, because they are extremely dangerous to public confidence. It has been suggested that the market is very short of gold, that the short positions may be a substantial multiple of the total amount of gold currently held by the Bank of England, and that the Bank’s real motive is to save the bacon of firms that are running those short positions. If such a suggestion is being made seriously, it must be dealt with authoritatively and definitively, and we want an answer from the Government now.

Apart from the question “Why do it?”, the obvious question in the minds of the public is, “Why do it in what is apparently such an incredibly incompetent and foolish fashion?”. Someone who is going to sell something does not announce it in advance to the world, and certainly does not try to talk down the price of a commodity in which he is rather long. In normal circumstances, that makes no sense. If these circumstances, or these rules, are abnormal, we had better hear why it is sensible to make a public announcement. On the facts, it is extremely foolish and damaging. As my hon. Friend the Member for Louth and Horncastle said, the markets have reduced the value of the whole gold reserve by 10 per cent. or more since the announcement, and it is clear that the announcement has been one of the major factors in the fall. This is, prima facie, a clear case of incompetence on the part of the new Labour Government.

As if that were not enough, how extraordinary it was to try to talk the International Monetary Fund into agreeing on a programme of gold sales a few weeks before trying to sell our own gold. That was madness. One has to be as incompetent as the Government appear to be to damage the market in advance of such a major sales operation. The Minister and, indeed, her boss the Chancellor, owe the taxpayer an explanation. Why have the taxpayer’s assets been squandered and their value gratuitously reduced? No sensible business man or woman would dream of conducting his or her affairs in such a way. Or is it perhaps that the conspiracy theory is right? Has the Government’s whole plan been simply to drive down the gold price by whatever means, fair or foul, to save the position of certain figures in the City—the firms that were hinted at by my hon. Friend the Member for Louth and Horncastle—which, apparently, are so short and potentially in such trouble? The Minister has an opportunity to throw light on that. I hope that she will do so.

Given the appalling mistake of having alerted the rest of the world that we were going to sell the gold, why did not the Minister think of alternative ways of proceeding? If she did, why did she not choose them? A private placing is one obvious route that I would have wanted to explore. Some central banks are buying gold. As their balance of payments improve, perhaps China and some of the far east countries will add to their reserves. We have already heard that the Bank of France and the other major gold holders are not selling. Perhaps they might have been prepared to buy a little more, particularly if the alternative was a public auction. They might have said, “We’ll help the British out a bit and take some.” The discount would almost certainly have been a good deal less than the 10 per cent. and more that has been the effective discount following the manner in which the Government decided to proceed.

Alternatively, what about “feeding the fix”—feeding the market over time? Was that alternative properly explored? If so, why was it not chosen? Of course, the amounts are significant, but, for years and years, the South Africans fed the fixing in the opposite direction. They sold their annual gold production over time, spreading it over the year. They found that to be a good way of doing things, so why, conversely, is it not a good way to reduce one’s gold reserves? We want to hear whether that potential solution was explored and, if so, why it was rejected.

Finally, what about the idea of a millennium issue—a retail issue of gold, not sovereigns? Each coin would presumably be much more valuable these days. That might have had distinct marketing opportunities at the millennium. Had we proceeded down that route, the Government might even have sold the gold at a premium and a discount would not have been necessary. Again, we want a clear explanation of why that route was not chosen.

10.52 am

The Economic Secretary to the Treasury (Ms Patricia Hewitt)

I congratulate the hon. Member for Louth and Horncastle (Sir P. Tapsell) on securing the debate and on his fascinating and wide-ranging speech, which, as the hon. Member for Grantham and Stamford (Mr. Davies) said, again displayed his skills and knowledge as a historian. I also congratulate the hon. Member for Grantham and Stamford on his promotion to the Front Bench. We heard in yesterday’s Finance Bill Committee that we were to lose two of the Front-Bench team from the Opposition. We welcome him and his colleagues to their new places.

In this extremely interesting debate, we have heard the two traditions, if you like, of attitudes towards gold. We have heard from the hon. Member for Louth and Horncastle of the mystical significance of gold—I was waiting for that word to appear and he did not disappoint me. During the sensible contributions of the hon. Members for Kingston and Surbiton (Mr. Davey) and for Chichester (Mr. Tyrie), we heard of the alternative view that was taken by Keynes in the 1930s—of gold as a “barbarous relic”.

I regret only that I have been left so little time to respond to the multiple points that have been raised, but I dismiss first the wilder rumours to which the hon. Members for Louth and Horncastle and for Grantham and Stamford both referred. They are nonsense. It is important that we do not in the House take at face value such absurd rumours, which occasionally float around the markets. We should be careful not to give currency to such rumours by remarks in the House that may verge on the irresponsible.

Several Members have asked why the Government have decided to restructure the reserves and to reduce our holdings in gold. The answer is simple. We have reviewed the nature of our portfolio—the assets that we hold in the reserves. We believe that the size of the holdings and their spread across currencies and gold should be determined by the balance of the risk and reward that is offered by gold, and how that compares with the other assets that are held in the reserves.

As some hon. Members have pointed out, gold has been a very poor investment over the past 20 years. The gold price in June 1979 was $280 dollars an ounce. It is little changed on that today, although it shot up to an unsustainable peak of some $800 an ounce in 1980. By contrast, other investments have offered capital gains, or reinvestment of substantial interest earnings over that period. What we are looking for in the restructuring of the reserves is a sensible diversification of the assets.

We are not saying that gold will continue to be a poor investment. As the hon. Member for Chichester said, none of us knows, but we would not be planning to retain a significant proportion of the reserves in gold if we believed that it had no place as a store of value. However, what has happened to the real value of gold should caution the House against some of the more exaggerated claims in its favour.

We continue to believe that gold is a valuable asset and that it performs an important role in countries’ reserve assets, but it has to justify its share in terms of its contribution to the overall balance of risks in our reserves portfolio. A key objective in that portfolio’s management is to minimise the risk to the taxpayer of fluctuations in the value of the reserves. Financing a large part of the reserves through borrowing in foreign currency largely eliminates that currency risk, as the hon. Member for Grantham and Stamford has acknowledged, but considerable risk is borne on the remaining net foreign currency and gold reserves, totalling the equivalent of $14 billion.

The hon. Member for Louth and Horncastle asked why we use that measure of net reserves. Perhaps I may draw his attention to the advice of the International Monetary Fund that countries should disclose not only their gross reserves, but their currency liabilities, so that a proper judgment can be arrived at of net reserves.

Almost half of this country’s net reserves have been held in the form of gold. Without taking a view on the prospects for gold, that is a very big exposure to a single asset. Reducing our gold holdings from 715 tonnes to some 300 tonnes over a number of years will gradually bring gold’s share of the net reserves down to about a fifth. We believe that that will achieve a better balance in the portfolio.

We will have a better diversified portfolio. We will not be as concentrated in gold as in the past. At the moment, we are twice as exposed to movements in the gold price as to movements in the value of the dollar. Therefore, it is a simple portfolio decision, designed to reduce the risk borne by the British taxpayer. The hon. Members for Louth and Horncastle and for Grantham and Stamford raised the question, as did other hon. Members, of the timing. The decision to sell now was not motivated by any view that the gold price was about to fall further, or by any of the wilder fantasies that have been suggested. The decision follows a careful review of the role for gold in the UK’s reserves. As I have said, it is about portfolio restructuring, not about playing the market, which the hon. Member for Grantham and Stamford seems to want us to do.

Of course we considered various routes for selling the gold before we decided that an auction programme offered advantages of transparency, spreading sales out over a lengthy period. If we had sold outside an auction process, we risked uncertainty over the timing of sales and much greater undermining of the gold price. If we had gone for covert sales on that scale, it is extremely likely that the sales would have been possible only at a discount to the market price. The House would rightly have been critical of such a course.

The gold market has become increasingly sensitised to central bank sales in recent years, of which, as some hon. Members have reminded us, there have been many throughout the world. There would have been a real danger that the market would have realised that a major central bank was selling and would have over-reacted to the volumes actually sold. As the Governor of the Bank of England has indicated, even with the orderly and transparent procedure that we have adopted, the market reaction has been somewhat overdone.

The Financial Times said there were three questions to ask about the—

Mr. Deputy Speaker (Mr. Michael J. Martin)

Order. We now come to the next debate.

Back to PRAYERS

Forward to Rail Network Integration (London)

© UK Parliament

We would like to thank the United Kingdom Parliamentary Archives for permission to reprint Sir Peter Tapsell’s speech before the House of Commons which contains Parliamentary information licensed under the Open Parliament Licence v3.0.

Image by UK Parliament [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons/Sir Peter Tapsell rises to speak in the House of Commons

A word on USAGOLD – USAGOLD ranks among the most reputable gold companies in the United States. Founded in the 1970s and still family-owned, it is one of the oldest and most respected names in the gold industry. USAGOLD has always attracted a certain type of investor – one looking for a high degree of reliability and market insight coupled with a professional client (rather than customer) approach to precious metals ownership. We are large enough to provide the advantages of scale, but not so large that we do not have time for you. (We invite your visit to the Better Business Bureau website to review our five-star, zero-complaint record. The report includes a large number of verified customer reviews.)

1-800-869-5115

[email protected]

Disclaimer – Opinions expressed on the USAGOLD.com website do not constitute an offer to buy or sell, or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any precious metals product, nor should they be viewed in any way as investment advice or advice to buy, sell or hold. USAGOLD, Inc. recommends the purchase of physical precious metals for asset preservation purposes, not speculation. Utilization of these opinions for speculative purposes is neither suggested nor advised. Commentary is strictly for educational purposes, and as such USAGOLD does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of the information found here.