GoldInfographic4

A Gold Classics Library Selection

The only “Why Gold” infographic you will ever need

by Jeff Desjardins/Visual Capitalist

Editor’s Note: This five-part infographic on gold [Links below] will educate and delight prospective and experienced gold owners alike. Not the stuff of dry economics, it reveals in roughly 15-minutes viewing time how gold came to be mankind’s most revered form of money and safe haven asset, and why it is likely to remain so for a long time to come.

The most sought after metal on Earth

Unearthing the world’s supply

The eclipsing demand of the East

The best reasons to own gold

Trends investors should be watching

Reprinted with permission.

A word on USAGOLD – USAGOLD ranks among the most reputable gold companies in the United States. Founded in the 1970s and still family-owned, it is one of the oldest and most respected names in the gold industry. USAGOLD has always attracted a certain type of investor – one looking for a high degree of reliability and market insight coupled with a professional client (rather than customer) approach to precious metals ownership. We are large enough to provide the advantages of scale, but not so large that we do not have time for you. (We invite your visit to the Better Business Bureau website to review our five-star, zero-complaint record. The report includes a large number of verified customer reviews.)

ORDER DESK

1-800-869-5115 Ext#100

[email protected]

Disclaimer – Opinions expressed on the USAGOLD.com website do not constitute an offer to buy or sell, or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any precious metals product, nor should they be viewed in any way as investment advice or advice to buy, sell or hold. USAGOLD, Inc. recommends the purchase of physical precious metals for asset preservation purposes, not speculation. Utilization of these opinions for speculative purposes is neither suggested nor advised. Commentary is strictly for educational purposes, and as such USAGOLD does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of the information found here.

GoldInfographic3

Gold Classics Library Selection

The only “Why Gold” infographic you will ever need

by Jeff Desjardins/Visual Capitalist

Editor’s Note: This five-part infographic on gold [Links below] will educate and delight prospective and experienced gold owners alike. Not the stuff of dry economics, it reveals in roughly 15-minutes viewing time how gold came to be mankind’s most revered form of money and safe haven asset, and why it is likely to remain so for a long time to come.

The most sought after metal on Earth

Unearthing the world’s supply

The eclipsing demand of the East

The best reasons to own gold

Trends investors should be watching

Reprinted with permission.

A word on USAGOLD – USAGOLD ranks among the most reputable gold companies in the United States. Founded in the 1970s and still family-owned, it is one of the oldest and most respected names in the gold industry. USAGOLD has always attracted a certain type of investor – one looking for a high degree of reliability and market insight coupled with a professional client (rather than customer) approach to precious metals ownership. We are large enough to provide the advantages of scale, but not so large that we do not have time for you. (We invite your visit to the Better Business Bureau website to review our five-star, zero-complaint record. The report includes a large number of verified customer reviews.)

ORDER DESK

1-800-869-5115 Ext#100

[email protected]

Disclaimer – Opinions expressed on the USAGOLD.com website do not constitute an offer to buy or sell, or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any precious metals product, nor should they be viewed in any way as investment advice or advice to buy, sell or hold. USAGOLD, Inc. recommends the purchase of physical precious metals for asset preservation purposes, not speculation. Utilization of these opinions for speculative purposes is neither suggested nor advised. Commentary is strictly for educational purposes, and as such USAGOLD does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of the information found here.

website support: [email protected] /

general mail: [email protected]

Site Map – Risk Disclosure – Privacy Policy – Shipping Policy – Terms of Use

© USAGOLD All Rights Reserved

Mailing Address –

P.O. Box 460009, Denver, CO USA 80246-0009

1-800-869-5115

GoldInfographic2

A Gold Classics Library Selection

The only “Why Gold” infographic you will ever need

by Jeff Desjardins/Visual Capitalist

Editor’s Note: This five-part infographic on gold [Links below] will educate and delight prospective and experienced gold owners alike. Not the stuff of dry economics, it reveals in roughly 15-minutes viewing time how gold came to be mankind’s most revered form of money and safe haven asset, and why it is likely to remain so for a long time to come.

The most sought after metal on Earth

Unearthing the world’s supply

The eclipsing demand of the East

The best reasons to own gold

Trends investors should be watching

Reprinted with permission.

A word on USAGOLD – USAGOLD ranks among the most reputable gold companies in the United States. Founded in the 1970s and still family-owned, it is one of the oldest and most respected names in the gold industry. USAGOLD has always attracted a certain type of investor – one looking for a high degree of reliability and market insight coupled with a professional client (rather than customer) approach to precious metals ownership. We are large enough to provide the advantages of scale, but not so large that we do not have time for you. (We invite your visit to the Better Business Bureau website to review our five-star, zero-complaint record. The report includes a large number of verified customer reviews.)

ORDER DESK

1-800-869-5115 Ext#100

[email protected]

Disclaimer – Opinions expressed on the USAGOLD.com website do not constitute an offer to buy or sell, or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any precious metals product, nor should they be viewed in any way as investment advice or advice to buy, sell or hold. USAGOLD, Inc. recommends the purchase of physical precious metals for asset preservation purposes, not speculation. Utilization of these opinions for speculative purposes is neither suggested nor advised. Commentary is strictly for educational purposes, and as such USAGOLD does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of the information found here.

GoldInfographic1

Gold Classics Library Selection

The only “Why Gold” infographic you will ever need

by Jeff Desjardins/Visual Capitalist

Editor’s Note: This five-part infographic on gold [Links below] will educate and delight prospective and experienced gold owners alike. Not the stuff of dry economics, it reveals in roughly 15-minutes viewing time how gold came to be mankind’s most revered form of money and safe haven asset, and why it is likely to remain so for a long time to come.

The most sought after metal on Earth

Unearthing the world’s supply

The eclipsing demand of the East

The best reasons to own gold

Trends investors should be watching

Reprinted with permission.

A word on USAGOLD – USAGOLD ranks among the most reputable gold companies in the United States. Founded in the 1970s and still family-owned, it is one of the oldest and most respected names in the gold industry. USAGOLD has always attracted a certain type of investor – one looking for a high degree of reliability and market insight coupled with a professional client (rather than customer) approach to precious metals ownership. We are large enough to provide the advantages of scale, but not so large that we do not have time for you. (We invite your visit to the Better Business Bureau website to review our five-star, zero-complaint record. The report includes a large number of verified customer reviews.)

ORDER DESK

1-800-869-5115 Ext#100

[email protected]

Disclaimer – Opinions expressed on the USAGOLD.com website do not constitute an offer to buy or sell, or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any precious metals product, nor should they be viewed in any way as investment advice or advice to buy, sell or hold. USAGOLD, Inc. recommends the purchase of physical precious metals for asset preservation purposes, not speculation. Utilization of these opinions for speculative purposes is neither suggested nor advised. Commentary is strictly for educational purposes, and as such USAGOLD does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of the information found here.

GoldInfographic5

The only “Why Gold” infographic you will ever need

by Jeff Desjardins/Visual Capitalist

Editor’s Note: This five-part infographic on gold [Links below] will educate and delight prospective and experienced gold owners alike. Not the stuff of dry economics, it reveals in roughly 15-minutes viewing time how gold came to be mankind’s most revered form of money and safe haven asset, and why it is likely to remain so for a long time to come.

The most sought after metal on Earth

Unearthing the world’s supply

The eclipsing demand of the East

The best reasons to own gold

Trends investors should be watching

Reprinted with permission.

A word on USAGOLD – USAGOLD ranks among the most reputable gold companies in the United States. Founded in the 1970s and still family-owned, it is one of the oldest and most respected names in the gold industry. USAGOLD has always attracted a certain type of investor – one looking for a high degree of reliability and market insight coupled with a professional client (rather than customer) approach to precious metals ownership. We are large enough to provide the advantages of scale, but not so large that we do not have time for you. (We invite your visit to the Better Business Bureau website to review our five-star, zero-complaint record. The report includes a large number of verified customer reviews.)

ORDER DESK

1-800-869-5115 Ext#100

[email protected]

Disclaimer – Opinions expressed on the USAGOLD.com website do not constitute an offer to buy or sell, or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any precious metals product, nor should they be viewed in any way as investment advice or advice to buy, sell or hold. USAGOLD, Inc. recommends the purchase of physical precious metals for asset preservation purposes, not speculation. Utilization of these opinions for speculative purposes is neither suggested nor advised. Commentary is strictly for educational purposes, and as such USAGOLD does not warrant or guarantee the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of the information found here.

GoldClassicsLibraryIndex

Gold Classics Library

Timeless and treasured essays collected over our more

than two decades on the world wide web

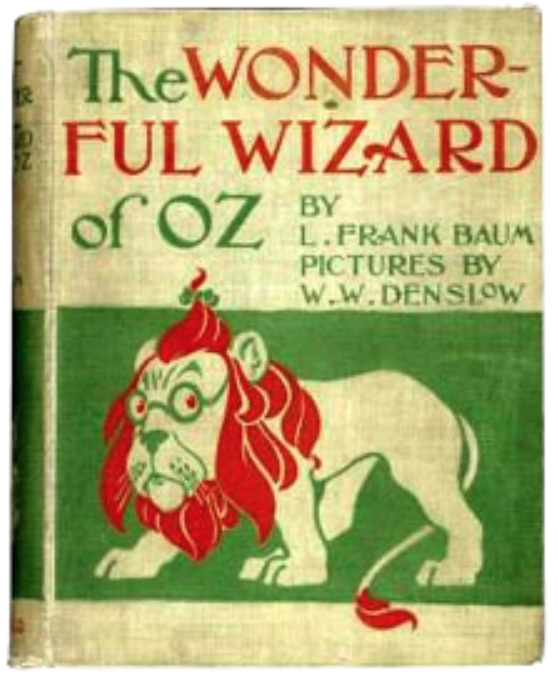

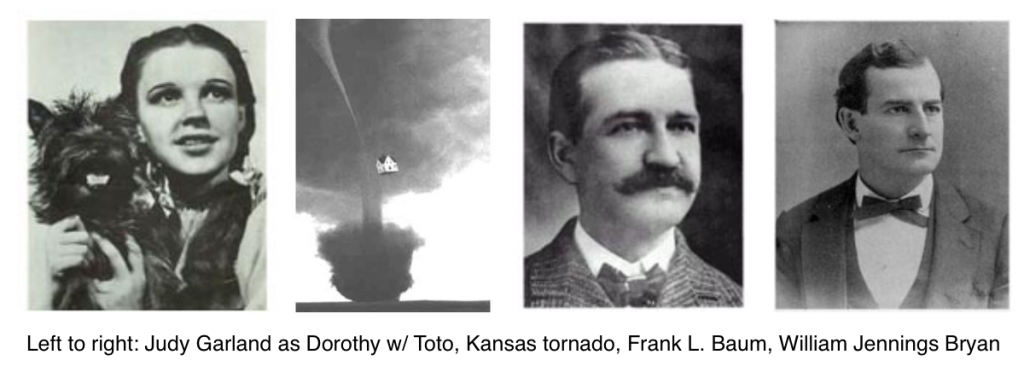

Money and Politics in the Land of Oz

by Quentin P. Taylor

L. Frank Baum claimed to have written The Wonderful Wizard of Oz “solely to pleasure the children” of his day, but scholars have found enough parallels between Dorothy’s yellow-brick odyssey and the politics of 1890s Populism to suggest otherwise. Did Baum intend to pen a subtle political satire on monetary reform?

Gold and Economic Freedom

by Alan Greenspan

“[T]he welfare statists were quick to recognize that if they wished to retain political power, the amount of taxation had to be limited and they had to resort to programs of massive deficit spending, i.e., they had to borrow money, by issuing government bonds, to finance welfare expenditures on a large scale.”

Who Owns and Controls the Federal Reserve?

by Dr. Edward Flaherty

Is the Federal Reserve System secretly owned and covertly controlled by powerful foreign banking interests? If so, how?

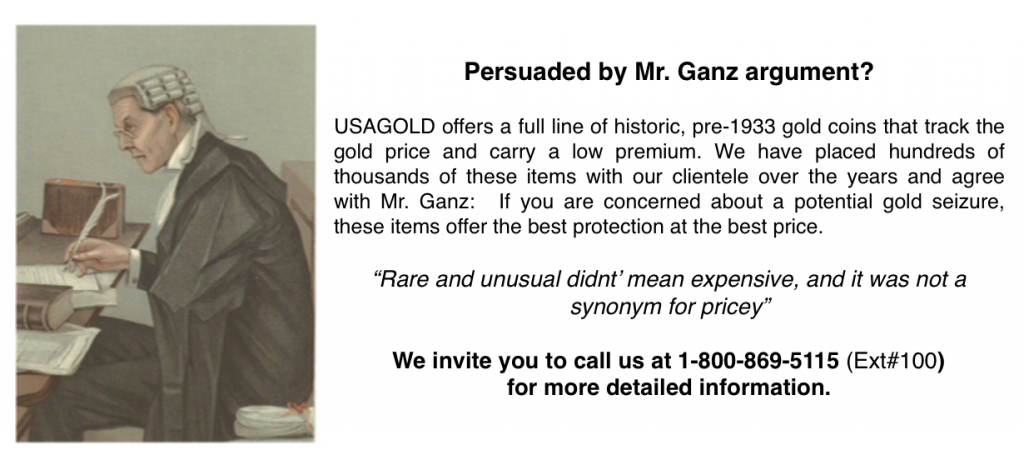

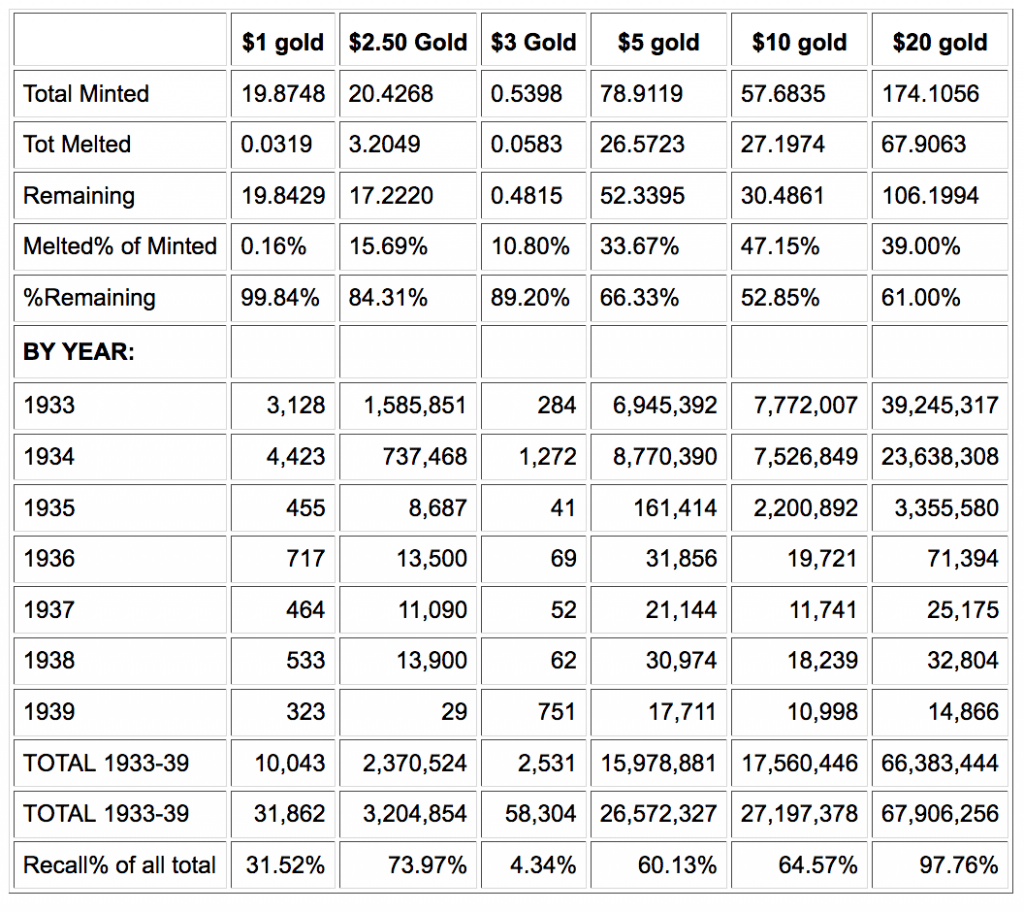

Gold Seizure: How it could happen and what you can do about it

by David L. Ganz, J.D.

Much has been offered in the way of opinion on the matter of a potential gold confiscation, but too little of it is well-researched, well-informed, and grounded in a true understanding of the laws and regulations involved. Herein the author, a prominent New York City attorney who specializes in numismatic and precious metals’ law and is often called upon by Congress to offer testimony in this regard, unravels past legal precedent and offers practical suggestions on a course of action for those concerned with the possibility of a contemporary confiscation.

Layman’s Guide to the Rules and Laws of Finance and Investment

by R.E.McMaster

There is an old saying that not all that glitters is gold — as in the gold coins many of you have held in your hands. There is another kind of gold that inhabits the practical wisdom of the ages. In today’s “go-get-’em,” “read-it-and-forget-it” world of everyday web browsing, it can be a challenge to separate the run of the mill from the meaningful.

Britain’s Gold Sales ‘a Reckless Act’

by Sir Peter Tapsell

In this speech before the House of Commons, June 16, 1999, Sir Peter Tapsell argued vigorously to keep the government from selling off over half of the country’s gold reserves. It remains one of the most eloquent speeches ever made on the merits of gold ownership for nation-states and individuals alike.

Alan Greenspan-Ron Paul Congressional Exchanges

The Congressional exchanges with Ron Paul Here we spotlight Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan’s remarkable and extended dialogue with Representative Dr. Ron Paul from 1997 – 2005 before the Congressional Committee on Financial Services.

The ‘Criterion’ Speech on Gold

by Charles DeGaulle

Delivered at the Palais de l’Élysée in 1965, Charles DeGaulle’s “Criterion” speech remains perhaps the most eloquent short discourse ever delivered on gold’s historical role as the final arbiter of value.

Fiat Money Inflation in France

by Andrew Dickson White

The famous study on the late 1700s runaway inflation in France. White reveals toward the end of the essay how those who had the wisdom to keep their savings in gold weathered the inflationary storm.

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

by Charles Mackay

We include this remarkable study with an agenda. If the rising generations now receiving their education, or even their more jaded elders, find application in their own investment philosophy, then the purpose of this Gilded Opinion entry has been served. Complicated and timelessly revealing, here you will find examples of herd behavior, delusion, mania, craftiness, and financial loss and gain.

Ten Rules For Investing In Gold

by John Hathaway

Gold is a controversial, anti-establishment investment. Therefore, do not rely on conventional financial media and brokerage house commentary. In this area, such commentary is even more misleading and ill-informed than usual.

The Scientific Tale of the Creation of Gold

by Robert Krulich

Only in a supernova is it possible to create atoms with 30 protons, 40 protons, 50 protons, or even 60 protons. Nature prefers even numbers for stability…Gold is a rare, odd-numbered atom with 79 protons.

Pompous Prognosticators

by Colin Seymour

Optimism was abundant as the stock market crash of 1929 unfolded. Seymour offers an oft-referenced chronology sure to raise an eyebrow.

Gresham’s Law in the History of Money

by Dr. Robert A. Mundell, 1999 Nobel Laureate

Gresham’s Law is not a statement about static conditions; it is a statement about a dynamic process. “Good money drives out bad if they exchange for the same price” is an acceptable expression of Gresham’s Law. But a better statement of it is that “Cheap money drives out dear if they exchange for the same price.”

The Only “Why Gold” Infographic You Will Ever Need

by Jeff Desjardins

This five-part infographic on gold will educate and delight prospective and experienced gold owners alike. Not the stuff of dry economics, it reveals in roughly 15-minutes viewing time how gold came to be mankind’s most revered form of money and safe-haven asset, and why it is likely to remain so for a long time to come.

A word on USAGOLD – USAGOLD ranks among the most reputable gold companies in the United States. Founded in the 1970s and still family-owned, it is one of the oldest and most respected names in the gold industry. USAGOLD has always attracted a certain type of investor – one looking for a high degree of reliability and market insight coupled with a professional client (rather than customer) approach to precious metals ownership. We are large enough to provide the advantages of scale, but not so large that we do not have time for you. (We invite your visit to the Better Business Bureau website to review our five-star, zero-complaint record. The report includes a large number of verified customer reviews.)

1-800-869-5115

[email protected]

FiatMoneyInflationFrance

Gold Classics Library Selection

Fiat Money Inflation in France

How It Came, What It Brought, and How It Ended

by Andrew Dickson White

Foreword

(USAGOLD)

Andrew Dickson White ends his classic historical essay on hyperinflation, “Fiat Money Inflation in France,” with one of the more famous lines in economic literature: “There is a lesson in all this which it behooves every thinking man to ponder.” This lesson — that there is a connection between government over-issuance of paper money, inflation and the destruction of middle-class savings — has been so routinely ignored in the modern era that enlightened savers the world over wonder if public officials will ever learn it.

The list of nations succumbing to very high and/or hyperinflationary episodes since the French experience at the end of the 18th century is legion. Here are a few of the more notable occurrences:

1. The Greenback and Confederate states inflations in the United States during and after the Civil War between the States;

2. A rash of national hyperinflations after World War I including Russia (1921-1924, 213 percent annualized); Poland (1922-1924, 275 percent annualized); Austria (1921-1922, 134 percent annualized); Hungary (1922-24, 98 percent annualized) and the most famous of them all, the Nightmare German Inflation (1920-1923, 3.25 million percent annualized);

3. Another round of episodes during and after World War II including Greece (1943-1944, 8.55 billion percent annualized); Hungary (1945-1946, 4.19 quintillion percent annualized) and China (1949-1950, unmeasured);

4. A rash of post World War II episodes including two in Argentina, and one each in Brazil, Chile, Nicaragua, Bolivia, Peru, Poland, Russia/Ukraine and Yugoslavia/Serbia (1);

5. The Asian contagion (1997-1998) including Indonesia, Thailand, South Korea, the Philippines and Malaysia which managed to display deflationary and inflationary symptoms simultaneously.

According to an International Monetary Fund sponsored study by Stanley Fischer, Ratna Sahay and Carlos Veigh (2002), hyperinflations have been a rare commodity since 1947 and the dawn of the Keynesian era, but “much more common have been longer inflationary processes with inflation rates above 100 percent per annum.” These they classify as “very high inflation” episodes. The study finds that close to 20% of the 133 countries studied experienced inflations of that magnitude. The average duration of these episodes was 40 months with a minimum of 12 months and maximum of over 200 months.

Not covered in the study is the myriad of double-digit inflation episodes since World War II (like the 1970s inflation in the United States) even though these events carried significant political and economic implications for the countries affected. Quite often though, these lesser inflations served as preludes to more debilitating events at some point down the road. Other times, as in the United States, public policies were instituted to smother the inflationary fires before they reached the critical stage.

All in all, it is difficult not to classify inflations of any size and duration as significant to the middle class. Few of us would gain comfort from the fact that the inflation we were experiencing failed to transcend the 100% per annum threshold or failed to escalate to a state of hyperinflation. Just the specter of double-digit inflation is enough to provoke some judicious portfolio hedging.

In 2019, the famous Andrew Dickson White essay you are about to read will celebrate its 107th anniversary. How can something written over 100 years ago describing monetary events occurring almost 215 years ago in France carry relevance for investors in the United States (and the rest of the industrialized world) today? The short answer is that the United States increasingly appears to be traveling a path similar to that of France in 1789 when the debasement of the currency, as Dickson White so matter of factly tells us, left the bulk of the population penniless. Fisher-Sahay-Veigh conclude that “the link with the French revolution supports the view that hyperinflations are modern phenomena related to printing paper money in order to finance large fiscal deficits caused by wars, revolutions, the end of empires and the establishment of new states.” How many Americans would read those words without some degree of apprehension?

What makes this particular dollar inflation even more dangerous than the assignat inflation studied by Dickson White is the potentially corrosive effect it is having on the international economy as a whole. The French inflation was localized; the dollar inflation is internationalized transcending national boundaries and encompassing not just the world’s most powerful economies but, in one way or another, most of the world’s smaller, less-developed economies as well. Since the global village as a whole has never been in this situation before, it is difficult to determine how the current situation might resolve itself. Suffice it to say that the potential for an international dollar crisis is something about which we should all be concerned.

The Andrew Dickson White essay tells the story of how good men — with nothing but the noblest of intentions – can drag a nation into monetary chaos in service to a political end. Still, there is something else in Dickson White’s essay — something perhaps even more profound. Democratic institutions, he reminds us, well-meaning though they might be, have a fateful, almost pre-destined inclination to print money when backed to the wall by unpleasant circumstances. You will no doubt see in this essay the inescapable similarities between France then and the United States now.

Dickson White’s section sketching the hedging aspect of the roughly one-fifth gold ounce coin, the Louis d’Or during this tumultuous period speaks volumes. And after all is said and done, it might end up being the most important lesson of all. Gold, the one primary portfolio asset which is not another’s liability, was the best defense in France in 1795; it is likely we will rediscover that it is the best defense now.

– USAGOLD/Michael J. Kosares

by Andrew Dickson White

Introduction

As far back as just before our Civil War I made, in France and elsewhere, a large collection of documents which had appeared during the French Revolution, including newspapers, reports, speeches, pamphlets, illustrative material of every sort, and, especially, specimens of nearly all the Revolutionary issues of paper money — from notes of ten thousand livres to those of one sou.

Upon this material, mainly, was based a course of lectures then given to my students, first at the University of Michigan and later at Cornell University, and among these lectures, one on “Paper Money Inflation in France.”

This was given simply because it showed one important line of facts in that great struggle; and I recall, as if it were yesterday, my feeling of regret at being obliged to bestow so much care and labor upon a subject to all appearance so utterly devoid of practical value. I am sure that it never occurred, either to my Michigan students or to myself, that it could ever have any bearing on our own country. It certainly never entered into our minds that any such folly as that exhibited in those French documents of the eighteenth century could ever find supporters in the United States of the nineteenth.

Some years later, when there began to be demands for large issues of paper money in the United States, I wrought some of the facts thus collected into a speech in the Senate of the State of New York, showing the need of especial care in such dealings with financial necessities.

In 1876, during the “greenback craze,” General Garfield and Mr. S. B. Crittenden, both members of the House of Representatives at that time, asked me to read a paper on the same general subject before an audience of Senators and Representatives of both parties in Washington. This I did, and also gave it later before an assemblage of men of business at the Union League Club in New York.

Various editions of the paper were afterward published, among them, two or three for campaign purposes, in the hope that they might be of use in showing to what folly, cruelty, wrong and pain the passion for “fiat money” may lead.

Other editions were issued at a later period, in view of the principle involved in the proposed unlimited coinage of silver in the United States, which was, at bottom, the idea which led to that fearful wreck of public and private prosperity in France.

For these editions there was an added reason in the fact that the utterances of sundry politicians at that time pointed clearly to issues of paper money practically unlimited. These men were logical enough to see that it would be inconsistent to stop at the unlimited issue of silver dollars which cost really something when they could issue unlimited paper dollars which virtually cost nothing.

In thus exhibiting facts which Bishop Butler would have recognized as confirming his theory of “The Possible Insanity of States,” it is but just to acknowledge that the French proposal was vastly more sane than that made in our own country. Those French issues of paper rested not merely “on the will of a free people,” but on one-third of the entire landed property of France; on the very choicest of real property in city and country–the confiscated estates of the Church and of the fugitive aristocracy–and on the power to use the paper thus issued in purchasing this real property at very low prices.

I have taken all pains to be exact, revising the whole paper in the light of the most recent publications and giving my authority for every important statement, and now leave the whole matter with my readers.

At the request of a Canadian friend, who has expressed a strong wish that this work be brought down to date, I have again restudied the subject in the light of various works which have appeared since my earlier research,–especially Levasseur’s “Histoire des classes ouvrières et de l’industrie en France,”–one of the really great books of the twentieth century;–Dewarmin’s superb “Cent Ans de numismatique Française” and sundry special treatises. The result has been that large additions have been made regarding some important topics, and that various other parts of my earlier work have been made more clear by better arrangement and supplementary information.

ANDREW D. WHITE, Cornell University, September, 1912.

PART I

Early in the year 1789 the French nation found itself in deep financial embarrassment: there was a heavy debt and a serious deficit.

The vast reforms of that period, though a lasting blessing politically, were a temporary evil financially. There was a general want of confidence in business circles; capital had shown its proverbial timidity by retiring out of sight as far as possible; throughout the land was stagnation.

Statesmanlike measures, careful watching and wise management would, doubtless, have ere long led to a return of confidence, a reappearance of money and a resumption of business; but these involved patience and self-denial, and, thus far in human history, these are the rarest products of political wisdom. Few nations have ever been able to exercise these virtues; and France was not then one of these few.[2]

There was a general search for some short road to prosperity: ere long the idea was set afloat that the great want of the country was more of the circulating medium; and this was speedily followed by calls for an issue of paper money. The Minister of Finance at this period was Necker. In financial ability he was acknowledged as among the great bankers of Europe, but his was something more than financial ability: he had a deep feeling of patriotism and a high sense of personal honor.

The difficulties in his way were great, but he steadily endeavored to keep France faithful to those principles in monetary affairs which the general experience of modem times had found the only path to national safety. As difficulties arose the National Assembly drew away from him, and soon came among the members renewed suggestions of paper money: orators in public meetings, at the clubs and in the Assembly, proclaimed it a panacea–a way of “securing resources without paying interest.” Journalists caught it up and displayed its beauties, among these men, Marat, who, in his newspaper, “The Friend of the People,” also joined the cries against Necker, picturing him–a man of sterling honesty, who gave up health and fortune for the sake of France–as a wretch seeking only to enrich himself from the public purse.

Against this tendency toward the issue of irredeemable paper Necker contended as best he might. He knew well to what it always had led, even when surrounded by the most skillful guarantees. Among those who struggled to support ideas similar to his was Bergasse, a deputy from Lyons, whose pamphlets, then and later, against such issues exerted a wider influence, perhaps, than any others: parts of them seem fairly inspired. Any one to-day reading his prophecies of the evils sure to follow such a currency would certainly ascribe to him a miraculous foresight, were it not so clear that his prophetic power was due simply to a knowledge of natural laws revealed by history. But this current in favor of paper money became so strong that an effort was made to breast it by a compromise: and during the last months of 1789 and the first months of 1790 came discussions in the National Assembly looking to issues of notes based upon the landed property of the Church,–which was to be confiscated for that purpose. But care was to be taken; the issue was to be largely in the shape of notes of 1,000, 300 and 200 livres, too large to be used as ordinary currency, but of convenient size to be used in purchasing the Church lands; besides this, they were to bear interest and this would tempt holders to hoard them. The Assembly thus held back from issuing smaller obligations.

Remembrances of the ruin which had come from the great issues of smaller currency at an earlier day were still vivid. Yet the pressure toward a popular currency for universal use grew stronger and stronger. The finance committee of the Assembly reported that “the people demand a new circulating medium”; that “the circulation of paper money is the best of operations”; that “it is the most free because it reposes on the will of the people”; that “it will bind the interest of the citizens to the public good.”

The report appealed to the patriotism of the French people with the following exhortation: “Let us show to Europe that we understand our own resources; let us immediately take the broad road to our liberation instead of dragging ourselves along the tortuous and obscure paths of fragmentary loans.” It concluded by recommending an issue of paper money carefully guarded, to the full amount of four hundred million livres, and the argument was pursued until the objection to smaller notes faded from view. Typical in the debate on the whole subject, in its various phases, were the declarations of M. Matrineau. He was loud and long for paper money, his only fear being that the Committee had not authorized enough of it; he declared that business was stagnant, and that the sole cause was a want of more of the circulating medium; that paper money ought to be made a legal tender; that the Assembly should rise above prejudices which the failures of John Law’s paper money had caused, several decades before. Like every supporter of irredeemable paper money then or since, he seemed to think that the laws of Nature had changed since previous disastrous issues. He said: “Paper money under a despotism is dangerous; it favors corruption; but in a nation constitutionally governed, which itself takes care in the emission of its notes, which determines their number and use, that danger no longer exists.” He insisted that John Law’s notes at first restored prosperity, but that the wretchedness and ruin they caused resulted from their overissue, and that such an overissue is possible only under a despotism.[3]

M. de la Rochefoucauld gave his opinion that “the assignats will draw specie out of the coffers where it is now hoarded.[4]

On the other hand Cazalès and Maury showed that the result could only be disastrous. Never, perhaps, did a political prophecy meet with more exact fulfillment in every line than the terrible picture drawn in one of Cazalès’ speeches in this debate. Still the current ran stronger and stronger; Petion made a brilliant oration in favor of the report, and Necker’s influence and experience were gradually worn away.

Mingled with the financial argument was a strong political plea. The National Assembly had determined to confiscate the vast real property of the French Church,–the pious accumulations of fifteen hundred years. There were princely estates in the country, bishops’ palaces and conventual buildings in the towns; these formed between one-fourth and one-third of the entire real property of France, and amounted in value to at least two thousand million livres. By a few sweeping strokes all this became the property of the nation. Never, apparently, did a government secure a more solid basis for a great financial future.[5]

There were two special reasons why French statesmen desired speedily to sell these lands. First, a financial reason,–to obtain money to relieve the government. Secondly, a political reason,–to get this land distributed among the thrifty middle-classes, and so commit them to the Revolution and to the government which gave their title.

It was urged, then, that the issue of four hundred millions of paper, (not in the shape of interest-bearing bonds, as had at first been proposed, but in notes small as well as large), would give the treasury something to pay out immediately, and relieve the national necessities; that, having been put into circulation, this paper money would stimulate business; that it would give to all capitalists, large or small, the means for buying from the nation the ecclesiastical real estate, and that from the proceeds of this real estate the nation would pay its debts and also obtain new funds for new necessities: never was theory more seductive both to financiers and statesmen.

It would be a great mistake to suppose that the statesmen of France, or the French people, were ignorant of the dangers in issuing irredeemable paper money. No matter how skillfully the bright side of such a currency was exhibited, all thoughtful men in France remembered its dark side. They knew too well, from that ruinous experience, seventy years before, in John Law’s time, the difficulties and dangers of a currency not well based and controlled. They had then learned how easy it is to issue it; how difficult it is to check its overissue; how seductively it leads to the absorption of the means of the workingmen and men of small fortunes; how heavily it falls on all those living on fixed incomes, salaries or wages; how securely it creates on the ruins of the prosperity of all men of meagre means a class of debauched speculators, the most injurious class that a nation can harbor,–more injurious, indeed, than professional criminals whom the law recognizes and can throttle; how it stimulates overproduction at first and leaves every industry flaccid afterward; how it breaks down thrift and develops political and social immorality. All this France had been thoroughly taught by experience. Many then living had felt the result of such an experiment–the issues of paper money under John Law, a man who to this day is acknowledged one of the most ingenious financiers the world has ever known; and there were then sitting in the National Assembly of France many who owed the poverty of their families to those issues of paper. Hardly a man in the country who had not heard those who issued it cursed as the authors of the most frightful catastrophe France had then experienced.[6]

It was no mere attempt at theatrical display, but a natural impulse, which led a thoughtful statesman, during the debate, to hold up a piece of that old paper money and to declare that it was stained with the blood and tears of their fathers.

And it would also be a mistake to suppose that the National Assembly, which discussed this matter, was composed of mere wild revolutionists; no inference could be more wide of the fact. Whatever may have been the character of the men who legislated for France afterward, no thoughtful student of history can deny, despite all the arguments and sneers of reactionary statesmen and historians, that few more keen-sighted legislative bodies have ever met than this first French Constitutional Assembly. In it were such men as Sieyès, Bailly, Necker, Mirabeau, Talleyrand, DuPont de Nemours and a multitude of others who, in various sciences and in the political world, had already shown and were destined afterward to show themselves among the strongest and shrewdest men that Europe has yet seen.

But the current toward paper money had become irresistible. It was constantly urged, and with a great show of force, that if any nation could safely issue it, France was now that nation; that she was fully warned by her severe experience under John Law; that she was now a constitutional government, controlled by an enlightened, patriotic people,–not, as in the days of the former issues of paper money, an absolute monarchy controlled by politicians and adventurers; that she was able to secure every livre of her paper money by a virtual mortgage on a landed domain vastly greater in value than the entire issue; that, with men like Bailly, Mirabeau and Necker at her head, she could not commit the financial mistakes and crimes from which France had suffered under John Law, the Regent Duke of Orleans and Cardinal Dubois.

Oratory prevailed over science and experience. In April, 1790, came the final decree to issue four hundred millions of livres in paper money, based upon confiscated property of the Church for its security. The deliberations on this first decree and on the bill carrying it into effect were most interesting; prominent in the debate being Necker, Du Pont de Nemours, Maury, Cazalès, Petion, Bailly and many others hardly inferior. The discussions were certainly very able; no person can read them at length in the “Moniteur,” nor even in the summaries of the parliamentary history, without feeling that various modern historians have done wretched injustice to those men who were then endeavoring to stand between France and ruin.

This sum–four hundred millions, so vast in those days, was issued in assignats, which were notes secured by a pledge of productive real estate and bearing interest to the holder at three per cent. No irredeemable currency has ever claimed a more scientific and practical guarantee for its goodness and for its proper action on public finances. On the one hand, it had what the world recognized as a most practical security,–a mortgage an productive real estate of vastly greater value than the issue. On the other hand, as the notes bore interest, there seemed cogent reason for their being withdrawn from circulation whenever they became redundant.[7]

As speedily as possible the notes were put into circulation. Unlike those issued in John Law’s time, they were engraved in the best style of the art. To stimulate loyalty, the portrait of the king was placed in the center; to arouse public spirit, patriotic legends and emblems surrounded it; to stimulate public cupidity, the amount of interest which the note would yield each day to the holder was printed in the margin; and the whole was duly garnished with stamps and signatures to show that it was carefully registered and controlled.[8]

To crown its work the National Assembly, to explain the advantages of this new currency, issued an address to the French people. In this address it spoke of the nation as “delivered by this grand means from all uncertainty and from all ruinous results of the credit system.” It foretold that this issue “would bring back into the public treasury, into commerce and into all branches of industry strength, abundance and prosperity.”[9]

Some of the arguments in this address are worth recalling, and, among them, the following:–“Paper money is without inherent value unless it represents some special property. Without representing some special property it is inadmissible in trade to compete with a metallic currency, which has a value real and independent of the public action; therefore it is that the paper money which has only the public authority as its basis has always caused ruin where it has been established; that is the reason why the bank notes of 1720, issued by John Law, after having caused terrible evils, have left only frightful memories. Therefore it is that the National Assembly has not wished to expose you to this danger, but has given this new paper money not only a value derived from the national authority but a value real and immutable, a value which permits it to sustain advantageously a competition with the precious metals themselves.”[10]

But the final declaration was, perhaps, the most interesting. It was as follows:–

“These assignats, bearing interest as they do, will soon be considered better than the coin now hoarded, and will bring it out again into circulation.” The king was also induced to issue a proclamation recommending that his people receive this new money without objection.

All this caused great joy. Among the various utterances of this feeling was the letter of M. Sarot, directed to the editor of the Journal of the National Assembly, and scattered through France. M. Sarot is hardly able to contain himself as he anticipates the prosperity and glory that this issue of paper is to bring to his country. One thing only vexes him, and that is the pamphlet of M. Bergasse against the assignats; therefore it is after a long series of arguments and protestations, in order to give a final proof of his confidence in the paper money and his entire skepticism as to the evils predicted by Bergasse and others, M. Sarot solemnly lays his house, garden and furniture upon the altar of his country and offers to sell them for paper money alone.

There were, indeed, some gainsayers. These especially appeared among the clergy, who, naturally, abhorred the confiscation of Church property. Various ecclesiastics made speeches, some of them full of pithy and weighty arguments, against the proposed issue of paper, and there is preserved a sermon from one priest threatening all persons handling the new money with eternal damnation. But the great majority of the French people, who had suffered ecclesiastical oppression so long, regarded these utterances as the wriggling of a fish on the hook, and enjoyed the sport all the better.[11]

The first result of this issue was apparently all that the most sanguine could desire: the treasury was at once greatly relieved; a portion of the public debt was paid; creditors were encouraged; credit revived; ordinary expenses were met, and, a considerable part of this paper money having thus been passed from the government into the hands of the people, trade increased and all difficulties seemed to vanish. The anxieties of Necker, the prophecies of Maury and Cazalès seemed proven utterly futile. And, indeed, it is quite possible that, if the national authorities had stopped with this issue, few of the financial evils which afterwards arose would have been severely felt; the four hundred millions of paper money then issued would have simply discharged the function of a similar amount of specie. But soon there came another result: times grew less easy; by the end of September, within five months after the issue of the four hundred millions in assignats, the government had spent them and was again in distress.[12]

The old remedy immediately and naturally recurred to the minds of men. Throughout the country began a cry for another issue of paper; thoughtful men then began to recall what their fathers had told them about the seductive path of paper-money issues in John Law’s time, and to remember the prophecies that they themselves had heard in the debate on the first issue of assignats less than six months before.

At that time the opponents of paper had prophesied that, once on the downward path of inflation, the nation could not be restrained and that more issues would follow. The supporters of the first issue had asserted that this was a calumny; that the people were now in control and that they could and would check these issues whenever they desired.

The condition of opinion in the Assembly was, therefore, chaotic: a few schemers and dreamers were loud and outspoken for paper money; many of the more shallow and easy-going were inclined to yield; the more thoughtful endeavored to breast the current.

One man there was who could have withstood the pressure: Mirabeau. He was the popular idol,–the great orator of the Assembly and much more than a great orator,–he had carried the nation through some of its worst dangers by a boldness almost godlike; in the various conflicts he had shown not only oratorical boldness, but amazing foresight. As to his real opinion on an irredeemable currency there can be no doubt. It was the opinion which all true statesmen have held, before his time and since,–in his own country, in England, in America, in every modern civilized nation. In his letter to Cerutti, written in January, 1789, hardly six months before, he had spoken of paper money as “A nursery of tyranny, corruption and delusion; a veritable debauch of authority in delirium.” In one of his early speeches in the National Assembly he had called such money, when Anson covertly suggested its issue, “a loan to an armed robber,” and said of it: “that infamous word, paper money, ought to be banished from our language.” In his private letters written at this very time, which were revealed at a later period, he showed that he was fully aware of the dangers of inflation. But he yielded to the pressure: partly because he thought it important to sell the government lands rapidly to the people, and so develop speedily a large class of small landholders pledged to stand by the government which gave them their titles; partly, doubtless, from a love of immediate rather than of remote applause; and, generally, in a vague hope that the severe, inexorable laws of finance which had brought heavy punishments upon governments emitting an irredeemable currency in other lands, at other times, might in some way at this time, be warded off from France.[13]

The question was brought up by Montesquieu’s report on the 27th of August, 1790. This report favored, with evident reluctance, an additional issue of paper. It went on to declare that the original issue of four hundred millions, though opposed at the beginning, had proved successful; that assignats were economical, though they had dangers; and, as a climax, came the declaration: “We must save the country.”[14]

Upon this report Mirabeau then made one of his most powerful speeches. He confessed that he had at first feared the issue of assignats, but that he now dared urge it; that experience had shown the issue of paper money most serviceable; that the report proved the first issue of assignats a success; that public affairs had come out of distress; that ruin had been averted and credit established. He then argued that there was a difference between paper money of the recent issue and that from which the nation had suffered so much in John Law’s time; he declared that the French nation had now become enlightened and he added, “Deceptive subtleties can no longer mislead patriots and men of sense in this matter.” He then went on to say: “We must accomplish that which we have begun,” and declared that there must be one more large issue of paper, guaranteed by the national lands and by the good faith of the French nation. To show how practical the system was he insisted that just as soon as paper money should become too abundant it would be absorbed in rapid purchases of national lands; and he made a very striking comparison between this self- adjusting, self-converting system and the rains descending in showers upon the earth, then in swelling rivers discharged into the sea, then drawn up in vapor and finally scattered over the earth again in rapidly fertilizing showers. He predicted that the members would be surprised at the astonishing success of this paper money and that there would be none too much of it.

His theory grew by what it fed upon,–as the paper-money theory has generally done. Toward the close, in a burst of eloquence, he suggested that assignats be created to an amount sufficient to cover the national debt, and that all the national lands be exposed for sale immediately, predicting that thus prosperity would return to the nation and that an classes would find this additional issue of paper money a blessing.[15]

This speech was frequently interrupted by applause; a unanimous vote ordered it printed, and copies were spread throughout France. The impulse given by it permeated all subsequent discussion; Gouy arose and proposed to liquidate the national debt of twenty-four hundred millions,–to use his own words–“by one single operation, grand, simple, magnificent.”[16] This “operation” was to be the emission of twenty-four hundred millions in legal tender notes, and a law that specie should not be accepted in purchasing national lands. His demagogy bloomed forth magnificently. He advocated an appeal to the people, who, to use his flattering expression, “ought alone to give the law in a matter so interesting.” The newspapers of the period, in reporting his speech, noted it with the very significant remark, “This discourse was loudly applauded.”

To him replied Brillat-Savarin. He called attention to the depreciation of assignats already felt. He tried to make the Assembly see that natural laws work as inexorably in France as elsewhere; he predicted that if this new issue were made there would come a depreciation of thirty per cent. Singular, that the man who so fearlessly stood against this tide of unreason has left to the world simply a reputation as the most brilliant cook that ever existed! He was followed by the Abbe Goutes, who declared,–what seems grotesque to those who have read the history of an irredeemable paper currency in any country–that new issues of paper money “will supply a circulating medium which will protect public morals from corruption.”[17]

Into this debate was brought a report by Necker. He was not, indeed, the great statesman whom France especially needed at this time, of all times. He did not recognize the fact that the nation was entering a great revolution, but he could and did see that, come what might, there were simple principles of finance which must be adhered to. Most earnestly, therefore, he endeavored to dissuade the Assembly from the proposed issue; suggesting that other means could be found for accomplishing the result, and he predicted terrible evils. But the current was running too fast. The only result was that Necker was spurned as a man of the past; he sent in his resignation and left France forever.[18] The paper-money demagogues shouted for joy at his departure; their chorus rang through the journalism of the time. No words could express their contempt for a man who was unable to see the advantages of filling the treasury with the issues of a printing press. Marat, Hebert, Camille Desmoulins and the whole mass of demagogues so soon to follow them to the guillotine were especially jubilant.[19]

Continuing the debate, Rewbell attacked Necker, saying that the assignats were not at par because there were not yet enough of them; he insisted that payments for public lands be received in assignats alone; and suggested that the church bells of the kingdom be melted down into small money. Le Brun attacked the whole scheme in the Assembly, as he had done in the Committee, declaring that the proposal, instead of relieving the nation, would wreck it. The papers of the time very significantly say that at this there arose many murmurs. Chabroud came to the rescue. He said that the issue of assignats would relieve the distress of the people and he presented very neatly the new theory of paper money and its basis in the following words: “The earth is the source of value; you cannot distribute the earth in a circulating value, but this paper becomes representative of that value and it is evident that the creditors of the nation will not be injured by taking it.” On the other hand, appeared in the leading paper, the “Moniteur,” a very thoughtful article against paper money, which sums up all by saying, “It is, then, evident that all paper which cannot, at the will of the bearer, be converted into specie cannot discharge the functions of money.” This article goes on to cite Mirabeau’s former opinion in his letter to Cerutti, published in 1789,–the famous opinion of paper money as “a nursery of tyranny, corruption and delusion; a veritable debauch of authority in delirium.” Lablache, in the Assembly, quoted a saying that “paper money is the emetic of great states.”[20]

Boutidoux, resorting to phrasemaking, called the assignats _”un papier terre,”_ or “land converted into paper.” Boislandry answered vigorously and foretold evil results. Pamphlets continued to be issued,–among them, one so pungent that it was brought into the Assembly and read there,–the truth which it presented with great clearness being simply that doubling the quantity of money or substitutes for money in a nation simply increases prices, disturbs values, alarms capital, diminishes legitimate enterprise, and so decreases the demand both for products and for labor; that the only persons to be helped by it are the rich who have large debts to pay. This pamphlet was signed “A Friend of the People,” and was received with great applause by the thoughtful minority in the Assembly. Du Pont de Nemours, who had stood by Necker in the debate on the first issue of assignats, arose, avowed the pamphlet to be his, and said sturdily that he had always voted against the emission of irredeemable paper and always would.[21]

Far more important than any other argument against inflation was the speech of Talleyrand. He had been among the boldest and most radical French statesmen. He it was,–a former bishop,–who, more than any other, had carried the extreme measure of taking into the possession of the nation the great landed estates of the, Church, and he had supported the first issue of four hundred millions. But he now adopted a judicial tone–attempted to show to the Assembly the very simple truth that the effect of a second issue of assignats may be different from that of the first; that the first was evidently needed; that the second may be as injurious as the first was useful. He exhibited various weak points in the inflation fallacies and presented forcibly the trite truth that no laws and no decrees can keep large issues of irredeemable paper at par with specie.

In his speech occur these words: “You can, indeed, arrange it so that the people shall be forced to take a thousand livres in paper for a thousand livres in specie; but you can never arrange it so that a man shall be obliged to give a thousand livres in specie for a thousand livres in paper,–in that fact is embedded the entire question; and on account of that fact the whole system fails.”[22]

The nation at large now began to take part in the debate; thoughtful men saw that here was the turning Point between good and evil, that the nation stood at the parting of the ways. Most of the great commercial cities bestirred themselves and sent up remonstrances against the new emission,–twenty-five being opposed and seven in favor of it.

But eloquent theorists arose to glorify paper and among these, Royer, who on September 14, 1790, put forth a pamphlet entitled “Reflections of a patriotic Citizen on the issue of assignats,” in which he gave many specious reasons of the why the assignats could not be depressed, and spoke of the argument against them as “vile clamors of people bribed to affect public opinion.” He said to the National Assembly, “If it is necessary to create five thousand millions, and more, of the paper, decree such a creation gladly.” He, too, predicted, as many others had done, a time when gold was to lose all its value, since all exchanges would be made with this admirable, guaranteed paper, and therefore that coin would come out from the places where it was hoarded. He foretold prosperous times to France in case these great issues of paper were continued and declared these “the only means to insure happiness, glory and liberty to the French nation.” Speeches like this gave courage to a new swarm of theorists,–it began to be especially noted that men who had never shown any ability to make or increase fortunes for themselves abounded in brilliant plans for creating and increasing wealth for the country at large.

Greatest force of all, on September 27, 1790, came Mirabeau’s final speech. The most sober and conservative of his modern opponents speaks of its eloquence as “prodigious.” In this the great orator dwelt first on the political necessity involved, declaring that the most pressing need was to get the government lands into the hands of the people, and so to commit to the nation and against the old privileged classes the class of landholders thus created.

Through the whole course of his arguments there is one leading point enforced with all his eloquence and ingenuity–the excellence of the proposed currency, its stability and its security. He declares that, being based on the pledge of public lands and convertible into them, the notes are better secured than if redeemable in specie; that the precious metals are only employed in the secondary arts, while the French paper money represents the first and most real of all property, the source of all production, the land; that while other nations have been obliged to emit paper money, none have ever been so fortunate as the French nation, for the reason that none had ever before been able to give this landed security; that whoever takes French paper money has practically a mortgage to secure it,–and on landed property which can easily be sold to satisfy his claims, while other nations have been able only to give a vague claim on the entire nation. “And,” he ones, “I would rather have a mortgage on a garden than on a kingdom!”

Other arguments of his are more demagogical. He declares that the only interests affected will be those of bankers and capitalists, but that manufacturers will see prosperity restored to them. Some of his arguments seem almost puerile, as when he says, “If gold has been hoarded through timidity or malignity, the issue of paper will show that gold is not necessary, and it will then come forth.” But, as a whole, the speech was brilliant; it was often interrupted by applause; it settled the question. People did not stop to consider that it was the dashing speech of an orator and not the matured judgment of a financial expert; they did not see that calling Mirabeau or Talleyrand to advise upon a monetary policy, because they had shown boldness in danger and strength in conflict, was like summoning a prize-fighter to mend a watch.

In vain did Maury show that, while the first issues of John Law’s paper had brought prosperity, those that followed brought misery; in vain did he quote from a book published in John Law’s time, showing that Law was at first considered a patriot and friend of humanity; in vain did he hold up to the Assembly one of Law’s bills and appeal to their memories of the wretchedness brought upon France by them; in vain did Du Pont present a simple and really wise plan of substituting notes in the payment of the floating debt which should not form a part of the ordinary circulating medium; nothing could resist the eloquence of Mirabeau. Barnave, following, insisted that “Law’s paper was based upon the phantoms of the Mississippi; ours, upon the solid basis of ecclesiastical lands,” and he proved that the assignats could not depreciate further. Prudhomme’s newspaper poured contempt over gold as security for the currency, extolled real estate as the only true basis and was fervent in praise of the convertibility and self-adjusting features of the proposed scheme. In spite of all this plausibility and eloquence, a large minority stood firm to their earlier principles; but on the 29th of September, 1790, by a vote of 508 to 423, the deed was done; a bill was passed authorizing the issue of eight hundred millions of new assignats, but solemnly declaring that in no case should the entire amount put in circulation exceed twelve hundred millions. To make assurance doubly sure, it also provided that as fast as the assignats were paid into the treasury for land they should be burned, and thus a healthful contraction be constantly maintained. Unlike the first issue, these new notes were to bear no interest.[23]

Great were the plaudits of the nation at this relief. Among the multitudes of pamphlets expressing this joy which have come down to us the “Friend of the Revolution” is the most interesting. It begins as follows: “Citizens, the deed is done. The assignats are the keystone of the arch. It has just been happily put in position. Now I can announce to you that the Revolution is finished and there only remain one or two important questions. All the rest is but a matter of detail which cannot deprive us any longer of the pleasure of admiring this important work in its entirety. The provinces and the commercial cities which were at first alarmed at the proposal to issue so much paper money now send expressions of their thanks; specie is coming out to be joined with paper money. Foreigners come to us from all parts of Europe to seek their happiness under laws which they admire; and soon France, enriched by her new property and by the national industry which is preparing for fruitfulness, will demand still another creation of paper money.”

France was now fully committed to a policy of inflation; and, if there had been any question of this before, all doubts were removed now by various acts very significant as show- ing the exceeding difficulty of stopping a nation once in the full tide of a depreciating currency. The National Assembly had from the first shown an amazing liberality to all sorts of enterprises, wise or foolish, which were urged “for the good of the people.” As a result of these and other largesses the old cry of the “lack of a circulating medium” broke forth again; and especially loud were the clamors for more small bills. The cheaper currency had largely driven out the dearer; paper had caused small silver and copper money mainly to disappear; all sorts of notes of hand, circulating under the name of “confidence bills,” flooded France–sixty-three kinds in Paris alone. This unguaranteed currency caused endless confusion and fraud. Different districts of France began to issue their own assignats in small denominations, and this action stirred the National Assembly to evade the solemn pledge that the circulation should not go above twelve hundred millions and that all assignats returned to the treasury for lands should immediately be burned.[24] Within a short time there had been received into the treasury for lands one hundred and sixty million livres in paper. By the terms of the previous acts this amount of paper ought to have been retired. Instead of this, under the plea of necessity, the greater part of it was reissued in the form of small notes.

There was, indeed, much excuse for new issues of small notes, for, under the theory that an issue of smaller notes would drive silver out of circulation, the smallest authorized assignat was for fifty livres. To supply silver and copper and hold it in circulation everything was tried. Citizens had been spurred on by law to send their silverware and jewels to the mint. Even the king sent his silver and gold plate, and the churches and convents were required by law to send to the government melting pot all silver and gold vessels not absolutely necessary for public worship. For copper money the church bells were melted down. But silver and even copper continued to become more and more scarce. In the midst of all this, various juggleries were tried, and in November, 1790, the Assembly decreed a single standard of coinage, the chosen metal being silver, and the ratio between the two precious metals was changed from 15 1/2 to 1, to 14 1/2 to 1–but all in vain. It was found necessary to issue the dreaded small paper, and a beginning was made by issuing one hundred millions in notes of five francs, and, ere long, obedient to the universal clamor, there were issued parchment notes for various small amounts down to a single sou.[25]

Yet each of these issues, great or small, was but as a drop of cold water to a parched throat. Although there was already a rise in prices which showed that the amount needed for circulation had been exceeded, the cry for “more circulating medium” was continued. The pressure for new issues became stronger and stronger. The Parisian populace and the Jacobin Club were especially loud in their demands for them; and, a few months later, on June 19, 1791, with few speeches, in a silence very ominous, a new issue was made of six hundred millions more;–less than nine months after the former great issue, with its solemn pledges to keep down the amount in circulation. With the exception of a few thoughtful men, the whole nation again sang paeans.[26]

In this comparative ease of new issues is seen the action of a law in finance as certain as the working of a similar law in natural philosophy. If a material body fall from a height its velocity is accelerated, by a well-known law, in a constantly increasing ratio: so in issues of irredeemable currency, in obedience to the theories of a legislative body or of the people at large, there is a natural law of rapidly increasing emission and depreciation. The first inflation bills were passed with great difficulty, after very sturdy resistance and by a majority of a few score out of nearly a thousand votes; but we observe now that new inflation measures were passed more and more easily and we shall have occasion to see the working of this same law in a more striking degree as this history develops itself.

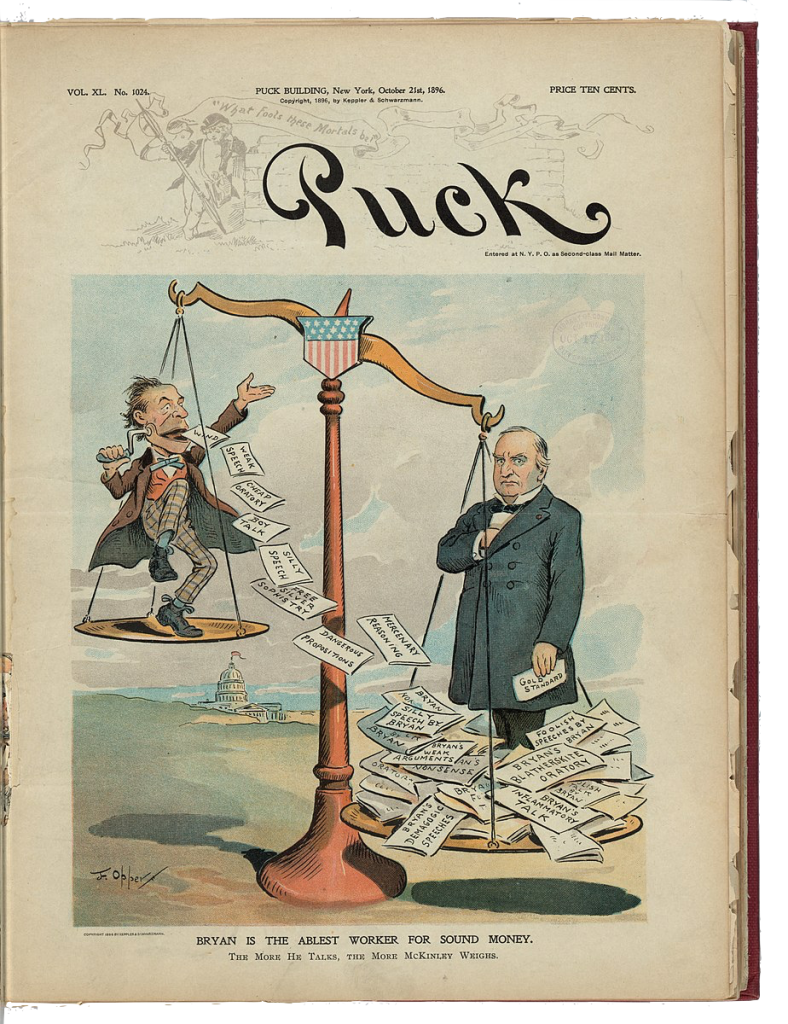

During the various stages of this debate there cropped up a doctrine old and ominous. It was the same which appeared toward the end of the nineteenth century in the United States during what became known as the “greenback craze” and the free “silver craze.” In France it had been refuted, a generation before the Revolution, by Turgot, just as brilliantly as it was met a hundred years later in the United States by James A. Garfield and his compeers. This was the doctrine that all currency, whether gold, paper, leather or any other material, derives its efficiency from the official stamp it bears, and that, this being the case, a government may relieve itself of its debts and make itself rich and prosperous simply by means of a printing press:–fundamentally the theory which underlay the later American doctrine of “fiat money.”

There came mutterings and finally speeches in the Jacobin Club, in the Assembly and in newspaper articles and pamphlets throughout the country, taking this doctrine for granted. These could hardly affect thinking men who bore in mind the calamities brought upon the whole people, and especially upon the poorer classes, by this same theory as put in practice by John Law, or as refuted by Turgot, but it served to swell the popular chorus in favor of the issue of more assignats and plenty of them.[27]

The great majority of Frenchmen now became desperate optimists, declaring that inflation is prosperity. Throughout France there came temporary good feeling. The nation was becoming inebriated with paper money. The good feeling was that of a drunkard just after his draught; and it is to be noted as a simple historical fact, corresponding to a physiological fact, that, as draughts of paper money came faster the successive periods of good feeling grew shorter.

Various bad signs began to appear. Immediately after each new issue came a marked depreciation; curious it is to note the general reluctance to assign the right reason. The decline in the purchasing power of paper money was in obedience to the simplest laws in economics, but France had now gone beyond her thoughtful statesmen and taken refuge in unwavering optimism, giving any explanation of the new difficulties rather than the right one. A leading member of the Assembly insisted, in an elaborate speech, that the cause of depreciation was simply the want of knowledge and of confidence among the rural population and he suggested means of enlightening them. La Rochefoucauld proposed to issue an address to the people showing the goodness of the currency and the absurdity of preferring coin. The address was unanimously voted. As well might they have attempted to show that a beverage made by mixing a quart of wine and two quarts of water would possess all the exhilarating quality of the original, undiluted liquid.

Attention was aroused by another menacing fact;–specie disappeared more and more. The explanations of this fact also displayed wonderful ingenuity in finding false reasons and in evading the true one. A very common explanation was indicated in Prudhomme’s newspaper, “Les Revolutions de Paris,” of January 17, 1791, which declared that coin “will keep rising until the people shall have hanged a broker.” Another popular theory was that the Bourbon family were, in some mysterious way, drawing off all solid money to the chief centers of their intrigues in Germany. Comic and, at the same time, pathetic, were evidences of the wide-spread idea that if only a goodly number of people engaged in trade were hanged, the par value of the assignats would be restored.

Still another favorite idea was that British emissaries were in the midst of the people, instilling notions hostile to paper. Great efforts were made to find these emissaries and more than one innocent person experienced the popular wrath under the supposition that he was engaged in raising gold and depressing paper. Even Talleyrand, shrewd as he was, insisted that the cause was simply that the imports were too great and the exports too little.[28] As well might he explain that fact that, when oil is mingled with water, water sinks to the bottom, by saying that this is because the oil rises to the top. This disappearance of specie was the result of a natural law as simple and as sure in its action as gravitation; the superior currency had been withdrawn because an inferior currency could be used.[29] Some efforts were made to remedy this. In the municipality of Quilleboeuf a considerable amount in specie having been found in the possession of a citizen, the money was seized and sent to the Assembly. The people of that town treated this hoarded gold as the result of unpatriotic wickedness or madness, instead of seeing that it was but the sure result of a law working in every land and time, when certain causes are present. Marat followed out this theory by asserting that death was the proper penalty for persons who thus hid their money.

Still another troublesome fact began now to appear. Though paper money had increased in amount, prosperity had steadily diminished. In spite of all the paper issues, commercial activity grew more and more spasmodic. Enterprise was chilled and business became more and more stagnant. Mirabeau, in his speech which decided the second great issue of paper, had insisted that, though bankers might suffer, this issue would be of great service to manufacturers and restore prosperity to them and their workmen. The latter were for a time deluded, but were at last rudely awakened from this delusion. The plenty of currency had at first stimulated production and created a great activity in manufactures, but soon the markets were glutted and the demand was diminished. In spite of the wretched financial policy of years gone by, and especially in spite of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, by which religious bigotry had driven out of the kingdom thousands of its most skillful Protestant workmen, the manufactures of France had before the Revolution come into full bloom. In the finer woolen goods, in silk and satin fabrics of all sorts, in choice pottery and porcelain, in manufactures of iron, steel, and copper, they had again taken their old leading place upon the Continent. All the previous changes had, at the worst, done no more than to inflict a momentary check on this highly developed system of manufactures. But what the bigotry of Louis XIV and the shiftlessness of Louis XV could not do in nearly a century, was accomplished by this tampering with the currency in a few months. One manufactory after another stopped. At one town, Lodève, five thousand workmen were discharged from the cloth manufactories. Every cause except the right one was assigned for this. Heavy duties were put upon foreign goods; everything that tariffs and custom-houses could do was done. Still the great manufactories of Normandy were closed, those of the rest of the kingdom speedily followed, and vast numbers of workmen in all parts of the country were thrown out of employment.[30] Nor was this the case with the home demand alone. The foreign demand, which at first had been stimulated, soon fell off. In no way can this be better stated than by one of the most thoughtful historians of modern times, who says, “It is true that at first the assignats gave the same impulse to business in the city as in the country, but the apparent improvement had no firm foundation, even in the towns. Whenever a great quantity of paper money is suddenly issued we invariably see a rapid increase of trade. The great quantity of the circulating medium sets in motion all the energies of commerce and manufactures; capital for investment is more easily found than usual and trade perpetually receives fresh nutriment. If this paper represents real credit, founded upon order and legal security, from which it can derive a firm and lasting value, such a movement may be the starting point of a great and widely-extended prosperity, as, for instance, a splendid improvement in English agriculture was undoubtedly owing to the emancipation of the country bankers. If on the contrary, the new paper is of precarious value, as was clearly seen to be the case with the French assignats as early as February, 1791, it can confer no lasting benefits. For the moment, perhaps, business receives an impulse, all the more violent because every one endeavors to invest his doubtful paper in buildings, machines and goods, which, under all circumstances, retain some intrinsic value. Such a movement was witnessed in France in 1791, and from every quarter there came satisfactory reports of the activity of manufactures.”

“But, for the moment, the French manufacturers derived great advantage from this state of things. As their products could be so cheaply paid for, orders poured in from foreign countries to such a degree that it was often difficult for the manufacturers to satisfy their customers. It is easy to see that prosperity of this kind must very soon find its limit. . . . When a further fall in the assignats took place this prosperity would necessarily collapse, and be succeeded by a crisis all the more destructive the more deeply men had engaged in speculation under the influence of the first favorable prospects.”[31]

Thus came a collapse in manufacturing and commerce, just as it had come previously in France: just as it came at various periods in Austria, Russia, America, and in all countries where men have tried to build up prosperity on irredeemable paper.[32]

All this breaking down of the manufactures and commerce of the nation made fearful inroads on the greater fortunes; but upon the lesser, and upon the little properties of the masses of the nation who relied upon their labor, it pressed with intense severity. The capitalist could put his surplus paper money into the government lands and await results; but the men who needed their money from day to day suffered the worst of the misery. Still another difficulty appeared. There had come a complete uncertainty as to the future. Long before the close of 1791 no one knew whether a piece of paper money representing a hundred livres would, a month later, have a purchasing power of ninety or eighty or sixty livres. The result was that capitalists feared to embark their means in business. Enterprise received a mortal blow. Demand for labor was still further diminished; and here came a new cause of calamity: for this uncertainty withered all far-reaching undertakings. The business of France dwindled into a mere living from hand to mouth. This state of things, too, while it bore heavily upon the moneyed classes, was still more ruinous to those in moderate and, most of all, to those in straitened circumstances. With the masses of the people, the purchase of every article of supply became a speculation–a speculation in which the professional speculator had an immense advantage over the ordinary buyer. Says the most brilliant of apologists for French revolutionary statesmanship, “Commerce was dead; betting took its place.”[33]

Nor was there any compensating advantage to the mercantile classes. The merchant was forced to add to his ordinary profit a sum sufficient to cover probable or possible fluctuations in value, and while prices of products thus went higher, the wages of labor, owing to the number of workmen who were thrown out of employment, went lower.